ByMIKE MCRAE

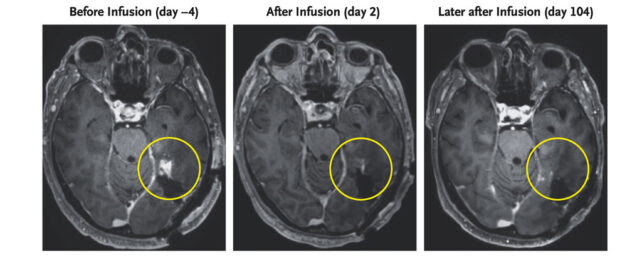

MRI scan of 72-year-old glioblastoma patient. (Choi et al., NEMJ, 2024)

Brain scans of a 72-year-old man diagnosed with a highly aggressive form of cancer known as a glioblastoma have revealed a remarkable regression in his tumor’s size within days of receiving an infusion of an innovative new treatment.

Though the outcomes of two other participants with similar diagnoses were somewhat less positive, the case’s success still bodes well for the search for a way to effectively cure what is currently an incurable disease.

Glioblastomas are typically about as deadly as cancers can get. Emerging from supporting cells inside the central nervous system, they can rapidly develop into malignant masses that claim up to 95 percent of patient lives within five years.

Researchers from Mass General Cancer Centre in the US suspected a treatment based on the patient’s own immune system, known as CAR T-cell therapy, might succeed where other therapies fail.

Having been approved for treating blood cancers, CAR T-cell therapy’s impressive ability to sniff out cancerous cells just might present advantages in destroying glioblastomas.

Patient T-cells are collected and re-engineered to recognize identifying surface markers on the outside of cancer cells before being returned via an infusion, meaning CAR T-cell therapy is somewhat like employing a local bounty hunter to slip silently through the alleys in search of a wanted villain.

One marker prevalent across a range of glioblastomas, a mutated variant of a protein called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has potential as a target for CAR T-cell treatment. Unfortunately glioblastomas wear a variety of disguises that make the re-engineering process a real challenge.

To overcome this, researchers have found a way to encourage CAR T-cells to also produce antibodies that seek out non-variant EGFRs. While these proteins aren’t usually expressed by brain cells, they are found on cancer cells, providing an extra identifying feature for the recruited bounty hunters.

Preclinical laboratory trials found the T-cell-engaging antibody molecule (TEAM) therapy worked as expected at the site of a tumor, even recruiting other regulatory T-cells to join in the fight.

The Intraventricular CARv3-TEAM-E T-Cells in Patients with Glioblastoma (INCIPIENT) was a phase 1 clinical trial tasked to evaluate the safety of the process, as well as its potential as a treatment.

Just three patients were recruited, all diagnosed with a form of glioblastoma expressing the variant EGFR.

The first patient, a 74 year old man, had undergone standard medication and radiation treatment for his tumor, only to have it return a year later. A day after he received an infusion of CARv3-TEAM-E T-Cells, his prognosis was looking good with an MRI scan showing significant reduction in the mass’s size.

Just months later, the patient would be back on the operating table with subsequent scans showing the cancer had once again progressed.

It was a similar story for a 57 year old woman with a sizable glioblastoma growing in her left hemisphere. Though her tumor saw a near complete regression five days after the therapy, the cancer showed signs of bouncing back just a month later.

With no signs of the reduced cancer returning in the 72-year-old third participant, and side effects limited to a fever and some nodules briefly appearing in the lungs, the researchers are optimistic they have grounds to continue exploring their novel immunotherapeutic approach.

“Our study of CARv3-TEAM-E T cells provides proof of principle that multiple surface antigens can be targeted simultaneously with the use of CAR T-cells and confirms that EGFR is a suitable immunotherapeutic target in glioblastoma,” the team writes in their published report.

Without knowing the long-term prognosis of any of the patients, it’s premature to describe the treatment as a cure. Yet with further study and additional clinical trials, CAR-T cell therapy could give at least some patients diagnosed with the deadliest of cancers a glimmer of hope.

This research was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Leave a Reply