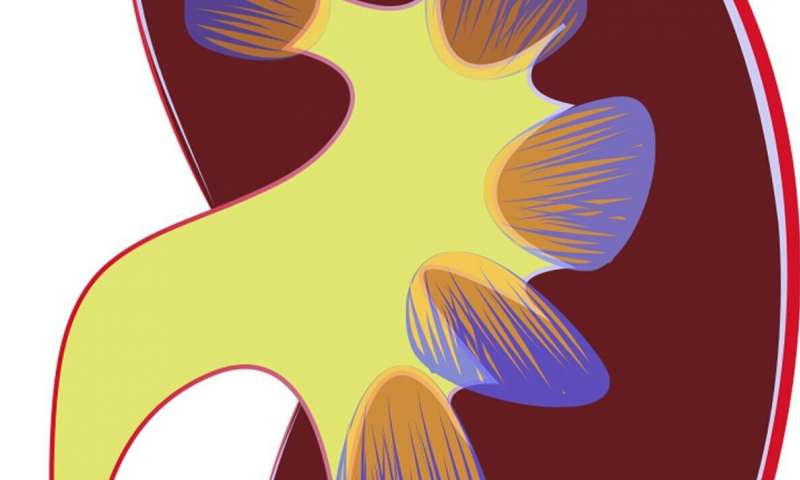

by American Society of Nephrology

A new study indicates that even early stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) can negatively impact individuals’ quality of life. The findings, which appear in an upcoming issue of CJASN, point to the importance of addressing, in addition to the medical aspects of chronic diseases, other factors that are important to patients.

A common perception of CKD is that patients are generally well until they require dialysis or a kidney transplant, but even patients with early stages of the disease may struggle with medical issues and declining quality of life. To provide a more accurate assessment of the quality of life in adults in India with mild-to-moderate CKD, a team led by Vivekanand Jha, MD (George Institute for Global Health) and Gopesh Modi, MD (Samarpan Kidney Institute and Research Center) examined data from the Indian Chronic Kidney Disease Study.

“There is almost no information on quality of life measurements in patients with CKD from low-middle income countries including India, which is home to about one-sixth of the world population and has over a million people with CKD,” said Dr. Jha. “The Indian Chronic Kidney Disease Study is the only large, multicentric prospective cohort of patients with CKD representing all parts of India. The primary objective of the study is to examine the natural history of CKD and the association of sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, and biological variables with clinical outcomes, including those important to patients.”

In the study, all patients had their quality of life assessed at baseline and annually. This included assessments of mental health, physical health, burden of kidney disease, symptoms and problems of kidney disease, and effects of kidney disease. “We found that between 15 and 22 out of every 100 Indian patients with mild-to-moderate CKD had significant impairment in at least 1 of the 5 domains of quality of life,” Dr. Jha said.

After adjusting for confounding factors, lower quality of life scores were associated with lower income, poor education, and female gender. “The findings point to the need to prioritize interventions targeted to these populations. Better understanding of the nature of these associations, and how they evolve over time—which will be ascertained in the follow-up phase of the study—will allow development of tailored interventions.”

An accompanying editorial assesses the study’s findings.

Leave a Reply