As the current COVID-19 situation shows, viruses are a major health risk. But what if we could fight them using other viruses? Scientists in Berlin have created virus shells that mimic the target cells that the flu virus latches onto in the body, preventing them from taking hold and causing infection.

Bacteriophages (or just phages) are types of viruses that prey on other microbes, usually bacteria. They’ve been explored as alternatives to antibiotics, and could come in many forms, such as inhalable treatments for pneumonia, dressings to sterilize wounds while they heal, antibacterial food wraps, or drinkable concoctions to treat food poisoning.

For the new study, the researchers pitted phages against other viruses. Rather than kill the invading virus, the phages instead act like a kind of trap. The team designed a phage to mimic the structures in lung cells that the flu virus binds to, rendering it ineffective.

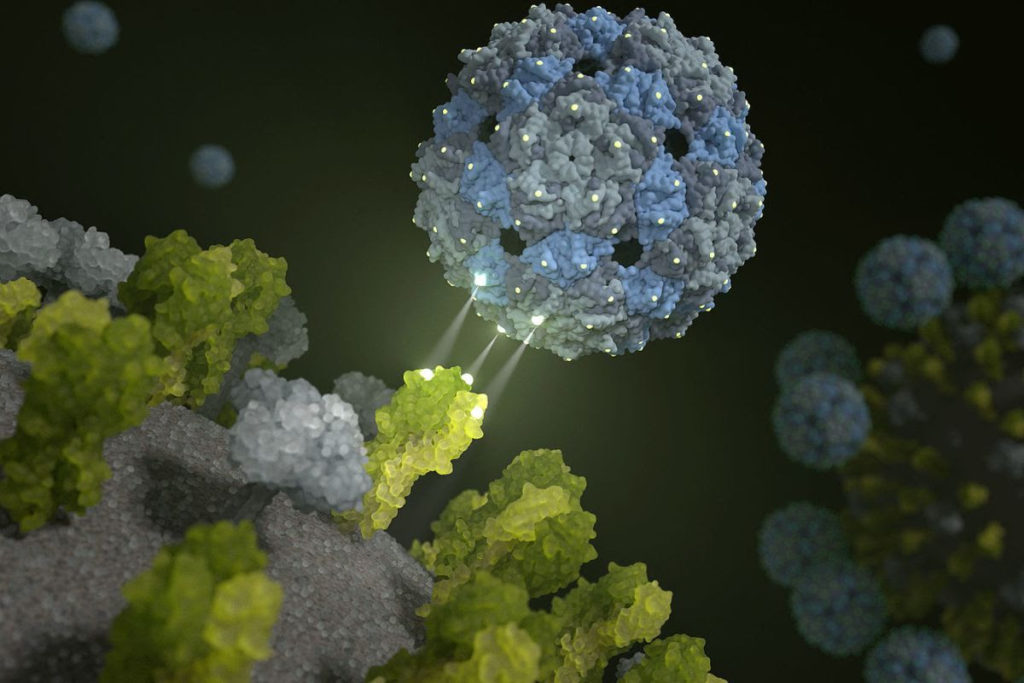

The surface of the flu virus is covered in receptors called hemagglutinin proteins, which latch onto sugar molecules on the surface of lung cells. Like a key in a lock, this is a very precise match that requires just the right number of bonds spaced apart at just the right intervals. So the team set out to design a decoy for the flu to bond to instead of lung cells.

The researchers started with a harmless intestinal phage called Q-beta, which already had a structure similar to what they needed. Using synthetic chemistry, the team equipped an empty Q-beta shell with sugar molecules in exactly the right arrangement. The end result is called a phage capsid.

“Our multivalent scaffold molecule is not infectious, and comprises 180 identical proteins that are spaced out exactly as the trivalent receptors of the hemagglutinin on the surface of the virus,” says Daniel Lauster, first author of the study. “It therefore has the ideal starting conditions to deceive the influenza virus – or, to be more precise, to attach to it with a perfect spatial fit. In other words, we use a phage virus to disable the influenza virus!”

Through mathematical models and cryo-electron microscope studies, the team was able to determine that the phage capsid completely encapsulated the virus, and was effective against several flu strains, including avian flu viruses. Tests in animal models and cell cultures showed that the phage capsid was able to neutralize the flu in human lung tissue, preventing it from reproducing.

“Pre-clinical trials show that we are able to render harmless both seasonal influenza viruses and avian flu viruses with our chemically modified phage shell,” says Christian Hackenberger, corresponding author of the study. “It is a major success that offers entirely new perspectives for the development of innovative antiviral drugs.”

As intriguing as the results are, the team says there’s still plenty of work to do before this new kind of treatment becomes available. A few important questions are still unanswered, such as whether the phages might trigger an immune response in people – and if so, whether that response helps or hinders the treatment. The flu might also develop resistance to the phages, which would put a damper on its usefulness. And that’s if it works in humans at all.

The team plans to continue working to address these issues and is also hopeful the technique could hold promise for the development of drugs that prevent infection of coronaviruses. Even if such a drug were developed, it would likely not be soon enough to help with the current pandemic, but could offer a potential weapon for any future coronavirus outbreaks.

The research was published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Source: Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V.

Leave a Reply