by University of California, Irvine

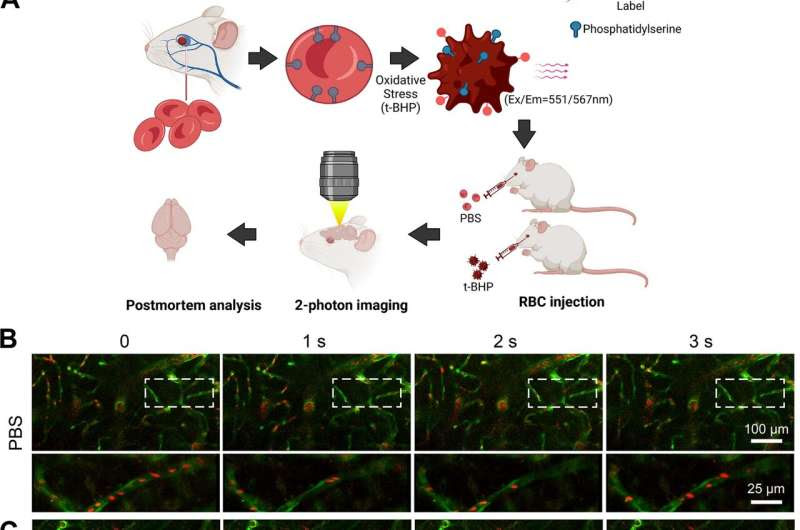

t-BHP-treated RBC stall in cerebral blood vessels and impair cerebral blood flow velocity shown by in vivo high-resolution two-photon imaging in mice. Schematic of the experimental design (A). RBC were collected from FVB/NJ mice, treated with control PBS or the oxidative stressor t-BHP, then labeled with the PKH26 fluorescent dye and injected intravenously into mice with Tie2-GFP-labeled endothelial vasculature. RBC (red) and cerebral blood vessels (green) were imaged in vivo using two-photon microscopy. Representative frames are shown at 1-s interval durations from control PBS-treated RBC-injected mice (B) and t-BHP-treated RBC-injected mice (C). The boxed areas are shown in the bottom panels of B and C, imaged at higher resolution and at different second intervals from parent images. RBC from the control PBS group exhibit robust flow in the cerebral blood vessels. In contrast, t-BHP-treated RBC stall significantly in cerebral blood vessels. Percentage of cerebral blood vessels with stalled RBC (D) and blood flow velocity (E) were measured at 1–4 h, 24 h, 5 days and 7 days after control versus t-BHP-treated RBC injections. Significantly more RBC stalls and reduced cerebral blood flow velocity are measured in mice injected with t-BHP-treated RBC relative to control PBS-treated RBC. Data are expressed at mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed with the LME. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Credit: Journal of Neuroinflammation (2023). DOI: 10.1186/s12974-023-02932-5

A first-of-its-kind study led by the University of California, Irvine has revealed a new culprit in the formation of brain hemorrhages that does not involve injury to the blood vessels, as previously believed. Researchers discovered that interactions between aged red blood cells and brain capillaries can lead to cerebral microbleeds, offering deeper insights into how they occur and identifying potential new therapeutic targets for treatment and prevention.

The findings, published online in the Journal of Neuroinflammation, describe how the team was able to watch the process by which red blood cells stall in the brain capillaries and then observe how the hemorrhage happens. Cerebral microbleeds are associated with a variety of conditions that occur at higher rates in older adults, including hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease and ischemic stroke.

“We have previously explored this issue in cell culture systems, but our current study is significant in expanding our understanding of the mechanism by which cerebral microbleeds develop,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Mark Fisher, professor of neurology in UCI’s School of Medicine. “Our findings may have profound clinical implications, as we identified a link between red blood cell damage and cerebral hemorrhages that occurs at the capillary level.”

The team exposed red blood cells to a chemical called tert-butyl hydroperoxide that caused oxidative stress; the cells were then marked with a fluorescent label and injected into mice. Using two different methods, the researchers observed the red blood cells getting stuck in the brain capillaries and then being cleared out in a process called endothelial erythrophagocytosis. As they moved out of the capillaries, microglia inflammatory cells engulfed the red blood cells, which led to the formation of a brain hemorrhage.

“It has always been assumed that in order for cerebral hemorrhage to occur, blood vessels need to be injured or disrupted. We found that increased red blood cell interactions with the brain capillaries represent an alternative source of development,” said co-corresponding author Xiangmin Xu, UCI professor of anatomy & neurobiology and director of the campus’s Center for Neural Circuit Mapping.

“We need to examine in detail the regulation of brain capillary clearance and also analyze how that process may be related to insufficient blood supply and ischemic stroke, which is the most common form of stroke, to help advance the development of targeted treatments.”

More information: Hai Zhang et al, Erythrocyte–brain endothelial interactions induce microglial responses and cerebral microhemorrhages in vivo, Journal of Neuroinflammation (2023). DOI: 10.1186/s12974-023-02932-5

Journal information: Journal of Neuroinflammation

Provided by University of California, Irvine

Leave a Reply