‘Lymphatic plexus’ behind the nose drains cerebrospinal fluid from the brain, potentially impacting neurodegenerative conditions –

In a groundbreaking study published in Nature, South Korean researchers led by Director KOH Gou Young of the Center for Vascular Research within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) have uncovered a distinctive network of lymphatic vessels at the back of the nose that plays a critical role in draining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain. The study, sheds light on a previously unknown route for CSF outflow, potentially unlocking new avenues for understanding and treating neurodegenerative conditions.

In our brains, waste products generated as byproducts of metabolic activity are expelled through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Accumulation of waste in the brain, if not properly expelled, can damage nerve cells, leading to impaired cognitive function, dementia, and other neurodegenerative brain disorders. Hence, the regulation of CSF production, circulation, and drainage has long been a focus of scientific attention, especially in relation to age-related conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases.

The brain produces around 500 mL of this fluid per day, which is drained from the subarachnoid space. Among the known drainage routes are lymphatic vessels around the cranial nerves and the upper region of the nasal cavity. Despite well-documented evidence of lymphatics aiding CSF clearance, identifying the exact anatomical connections between the subarachnoid space and extracranial lymphatics has posed a challenge due to their extremely complex structure.

Koh’s team tackled this problem using transgenic mice with lymphatic fluorescent markers, microsurgeries, and advanced imaging techniques. Their efforts revealed a detailed network of lymphatic vessels at the back of the nose that serves as a major hub for CSF outflow to deep cervical lymph nodes in the neck. These lymphatics were found to have distinct features, including unusually shaped valves and short lymphangions.

Lead researcher JIN Hokyung highlighted, “Our study identified the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus as a hub for CSF outflow. CSF from specific cranial regions drained through these lymphatics to deep cervical lymph nodes in the neck. This discovery could have significant implications for understanding and treating conditions related to impaired CSF drainage.”

The study also demonstrated that pharmacological activation of the deep cervical lymphatics enhanced CSF drainage in mice. The researchers were able to successfully modulate cervical lymphatics using phenylephrine (which activates α1-adrenergic receptors, causing smooth-muscle contraction) or sodium nitroprusside (which releases nitric oxide, inducing muscle relaxation and vessel dilation). Importantly, this feature was preserved during aging, even when the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus had shrunk and was functionally impaired.

YOON Jin-Hui, the co-first author of this study, notes, “The deep cervical lymphatics, which remain intact with aging, offer a potential target for therapeutic interventions aimed at improving CSF outflow in individuals with compromised brain health.”

This endeavor was not without its own challenges, however. Deep anesthesia and removal of neck musculature were required to expose the lymphatics in the mice. These delicate procedures themselves had problems altering the physiological dynamics of CSF drainage because cerebral blood flow and blood pulsing through the vasculature contribute to CSF circulation, which in turn influences CSF outflow. Also, while the imaging techniques used were informative, researchers believe more advanced methods for imaging live animals (such as synchrotron X-ray imaging) may reveal more features of the dynamics of CSF drainage under physiological conditions.

Director KOH Gou Young of the Center for Vascular Research stated, “We plan to verify all the findings from the mice in primates, including monkeys and humans. We aim to investigate in a reliable animal model whether activating the cervical lymphatic vessels through pharmacological or mechanical means can prevent the exacerbation of Alzheimer’s disease progression by improving CSF clearance.”

The results of this research have been published online on January 11th in the journal Nature (IF 69.504). It also has been published in print in the January 25th issue of Nature, featured as a cover titled “BRAIN DRAIN”.

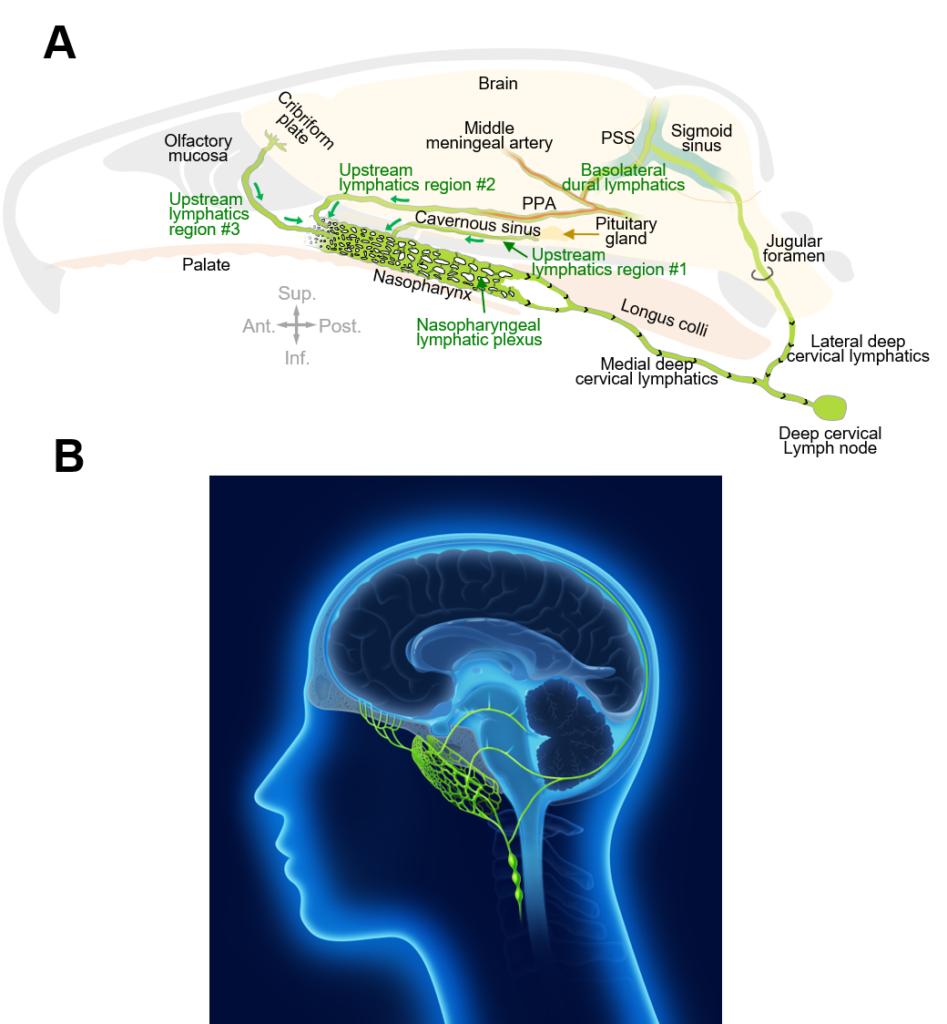

Figure 1. Connections of nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus and features of deep cervical lymphatics

A. The drawing shows intracranial upstream lymphatic regions #1, #2, and #3 that drain through the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus (NPLP) en route to medial deep cervical lymphatics and deep cervical lymph nodes in mice. Upstream lymphatic region #1 includes lymphatics near the pituitary gland and cavernous sinus that drain to the NPLP. Upstream lymphatic region #2 includes lymphatics in the anterior region of the basolateral dura near the middle meningeal artery and petrosquamosal sinus (PSS) that course along the pterygopalatine artery (PPA) to the NPLP. Upstream lymphatic region #3 includes lymphatics near the cribriform plate that drain to lymphatics in the olfactory mucosa en route to the posterior nasal lymphatic plexus and NPLP. In contrast, lymphatics in the posterior region of the basolateral dura around the sigmoid sinus do not drain to the NPLP but instead, pass through the jugular foramen to lateral deep cervical lymphatics en route to deep cervical lymph nodes. Anatomical positions are indicated in the lower corner. Ant., anterior; Post., posterior; Sup., superior; Inf., inferior anatomical position.

B. The drawing highlights the lymphatic connections of the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus to the deep cervical lymphatics and deep cervical lymph nodes for cerebrospinal fluid in humans, based on the findings obtained from the mice and monkeys in this study.

Figure 1. Connections of nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus and features of deep cervical lymphatics

A. The drawing shows intracranial upstream lymphatic regions #1, #2, and #3 that drain through the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus (NPLP) en route to medial deep cervical lymphatics and deep cervical lymph nodes in mice. Upstream lymphatic region #1 includes lymphatics near the pituitary gland and cavernous sinus that drain to the NPLP. Upstream lymphatic region #2 includes lymphatics in the anterior region of the basolateral dura near the middle meningeal artery and petrosquamosal sinus (PSS) that course along the pterygopalatine artery (PPA) to the NPLP. Upstream lymphatic region #3 includes lymphatics near the cribriform plate that drain to lymphatics in the olfactory mucosa en route to the posterior nasal lymphatic plexus and NPLP. In contrast, lymphatics in the posterior region of the basolateral dura around the sigmoid sinus do not drain to the NPLP but instead, pass through the jugular foramen to lateral deep cervical lymphatics en route to deep cervical lymph nodes. Anatomical positions are indicated in the lower corner. Ant., anterior; Post., posterior; Sup., superior; Inf., inferior anatomical position.

B. The drawing highlights the lymphatic connections of the nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus to the deep cervical lymphatics and deep cervical lymph nodes for cerebrospinal fluid in humans, based on the findings obtained from the mice and monkeys in this study.

Figure 2. Cover image

The study “Nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus is a hub for cerebrospinal fluid drainage” has been selected as the cover image of the January 25th, 2024 issue of Nature.

Figure 2. Cover image

The study “Nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus is a hub for cerebrospinal fluid drainage” has been selected as the cover image of the January 25th, 2024 issue of Nature.

Notes for editors

References

Jin-Hui Yoon, Hokyung Jin, Hae Jin Kim, Seon Pyo Hong, Myung Jin Yang, Ji Hoon Ahn, Young-Chan Kim, Jincheol Seo, Yongjeon Lee, Donald M. McDonald, Michael J. Davis, Gou Young Koh. Nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus is a hub for cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06899-4

Media Contact

For further information or to request media assistance, please contact Jin-Hui Yoon, Hokyung Jin, or Gou Young Koh at the Center for Vascular Research, Institute for Basic Science (IBS) ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) or William I. Suh at the IBS Public Relations Team ([email protected]).

About the Institute for Basic Science (IBS)

IBS was founded in 2011 by the government of the Republic of Korea with the sole purpose of driving forward the development of basic science in South Korea. IBS has 7 research institutes and 30 research centers as of January 2024. There are eight physics, three mathematics, five chemistry, seven life science, two earth science, and five interdisciplinary research centers.

Leave a Reply