by American Heart Association

Karthik Gonuguntla et al, Proportionate Mortality of Premature Myocardial Infarction in American Indians and Alaska Natives in the USA From 1999-2020. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/?_ga=2.17782015.7532578.1693882428-1949139275.1663003561#!/10871/presentation/12322

American Indian and Alaska Native adults had significantly higher heart attack death rates at younger ages compared to adults in other racial and ethnic group, according to preliminary research to be presented at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2023. The meeting, to be held Nov. 11–13, in Philadelphia, is a premier global exchange of the latest scientific advancements, research and evidence-based clinical practice updates in cardiovascular science.

“Despite ongoing initiatives aimed at reducing health disparities among people of underrepresented races and ethnicities, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native adults, and they have disproportionately higher rates of heart attacks at a younger age,” said study lead author Karthik Gonuguntla, M.D., a cardiology fellow at West Virginia University. “However, most studies either exclude American Indian and Alaska Native populations in their analysis or combine them with all ‘other’ races, making these populations typically understudied.”

The researchers reviewed data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research (CDC WONDER) database to investigate death trends related to premature heart attacks among American Indian and Alaska Native populations from 1999 to 2020. Premature heart attacks were defined as those that occur in men younger than age 55 and women younger than age 65. The WONDER database aggregates death certificate data across the U.S. from the National Vital Statistics System.

The analysis found:

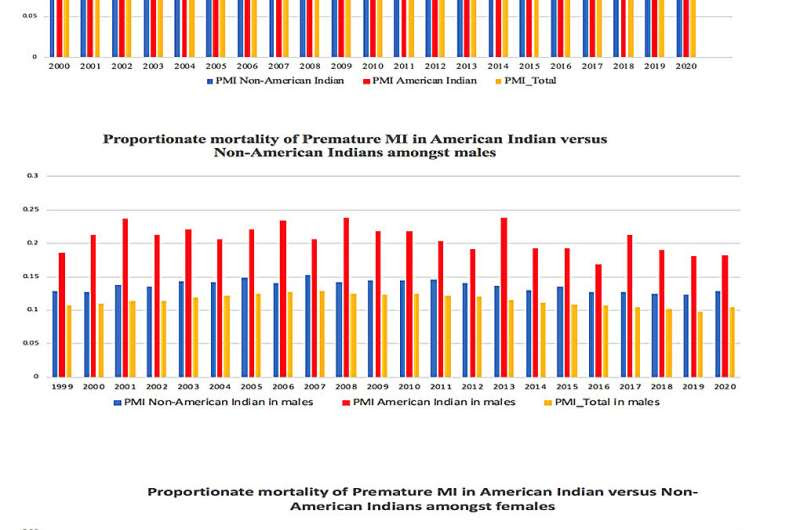

The overall death rate from premature heart attacks was 23% among American Indian and Alaska Native adults, compared to 15% among white, Black and Asian/Pacific Islander adults.

American Indian and Alaska Native men younger than age 55 had a 21% heart attack death rate, compared to 14% of white, Black and Asian/Pacific Islander men.

American Indian and Alaska Native women younger than age 65 had a 26% heart attack death rate, compared to 16% among women of other races.

“There’s a possibility that younger age group patients in the American Indian and Alaska Native communities are not well screened and/or treated for risk factors for heart attack, such as high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes and/or substance use disorder,” Gonuguntla said. “Chest pain may also be attributed to other non-heart related causes in younger populations and not managed in a time-sensitive manner. This delay in care may have led to higher premature heart attack deaths.”

The higher death rates among American Indian and Alaska Native populations may also be explained by the increased prevalence of heart disease risk factors in this group, as well as restricted health care access, limited health insurance coverage, lower socioeconomic conditions and/or exposure to chronic stress, the authors noted.

“Women and people from Indigenous racial and ethnic groups face persistent disparities in triage, diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular disease,” Gonuguntla said. “It’s important to focus on the social determinants of health that could be playing a role and implement various strategies at both the state and national level to address them.”

Study background and details:

The study included 373,317 premature heart attack deaths in the U.S. from 1999 to 2020, 14,055 of which were among American Indian and Alaska Native adults.

The study authors found no significant improvement over time in the proportionate number of deaths from heart attacks among the American Indian/Alaska Native population when analyzing all adults together. However, American Indian/Alaska Native women had a non-statistically significant increase in the proportionate number of deaths from heart attacks from 21.6% in 1999 to 27.3% in 2020, while males had a statistically significant decrease in proportionate number of deaths from heart attack from 18.5% in 1999 to 18.2% in 2020.

“Even though it looks like the number of deaths in women increased, our analysis found it was not significant,” Gonuguntla said. “These findings, however, are a signal that more work is needed to reverse this trend among American Indian/Alaska Native women.”

The study’s limitations included that causes of death noted on death certificates may have some miscoding errors, therefore, it would affect the data analysis since deaths attributable to acute heart attacks were the original data source. In addition, the authors did not include secondary causes of death analysis for the abstract and they did not have information regarding CVD risk factors, family histories of CVD or initial measurements of other health conditions (such as hypertension and/or Type 2 diabetes diagnosis).

The source data in the WONDER database does not include clinical information about patients, such as if there was a history of cardiovascular interventions like percutaneous coronary intervention or mechanical complications, both of which may increase the risk of acute heart attack.

“With over 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S., it is impossible for one such as myself to speak for all American Indian/Alaska Native people. However, the data are compelling and show high rates of preventable illness at younger ages than in other populations,” said Allison Kelliher, M.D., a research associate at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and a senior research associate at the Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Indigenous Health, both in Baltimore.

Kelliher, who is Koyukon Athabascan, Dena, from Nome, Alaska, is vice chair of the Association’s 2023 scientific statement Status of Maternal Cardiovascular Health in American Indian and Alaska Native Individuals and founder and former director of the American Indian Collaborative Research Network (AICoRN).

“As a family physician, biomedical researcher and Traditional Alaska Native Healer, I see ways that we can adapt and implement appropriate and successful programs to prevent and treat tobacco use, more effectively promote healthy body weight and address other factors that increase our risk of cardiovascular disease, such as cholesterol, blood sugar and blood pressure.

“We need to better develop culturally safe and appropriate programs and supports that are effective and accessible,” she said. “In addition, we have an opportunity here, especially in informed Alaska Indigenous/Alaska Native communities, to work toward addressing our own individual and collective heart health.”

Provided by American Heart Association

Leave a Reply