by Marie Simon, Paris Brain Institute

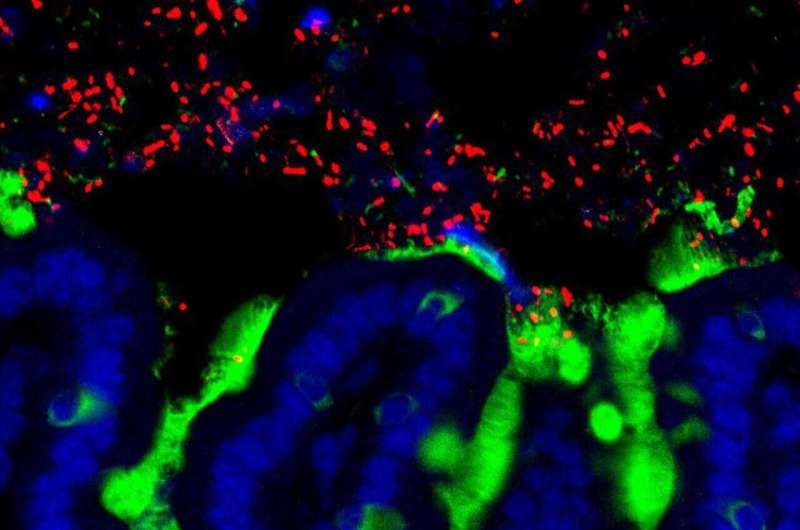

Commensal bacteria (red) among the mucus (green) and epithelial cells (blue) in a mouse small intestine. Credit: University of Chicago.

The way we make decisions in a social context can be explained by psychological, social, and political factors. But what if other forces were at work? Hilke Plassmann and her colleagues from the Paris Brain Institute and the University of Bonn show that changes in gut microbiota can influence our sensitivity to fairness and how we treat others. Their findings are published in the journal PNAS Nexus.

The intestinal microbiota—i.e., all the bacteria, viruses and fungi that inhabit our digestive tract—plays a pivotal role in our bodies, well beyond digestive function. Recent research underscores its impact on cognition, stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and behavior; mice raised in a sterile environment, for example, have difficulty interacting with other individuals.

While these findings are promising, most of this research is carried out on animals and cannot be extrapolated to humans. Nor does it allow us to understand what neuronal, immune, or hormonal mechanisms are at work in this fascinating dialogue between brain and intestine: researchers observe a link between the composition of the microbiota and social skills but do not know precisely how one controls the other.

“The available data suggests that the intestinal ecosystem communicates with the central nervous system via various pathways, including the vagus nerve,” explains Plassmann (Sorbonne University), head of the Control-Interoception-Attention Team at the Paris Brain Institute, and professor at Insead. “It might also use biochemical signals that trigger the release of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin, which are essential for proper brain function.”

Studying altruistic punishment

To determine whether the composition of the human gut microbiota could influence decision-making in a social setting, the researcher and her colleagues used behavioral tests—including the famous “ultimatum game” in which one player is given a sum of money he must split (fairly or unfairly) with a second player, who is free to decline the offer if she deems it insufficient. In that case, neither player receives any money.

Refusing the sum of money is equivalent to what we call “altruistic punishment,” i.e., the impulse to punish others when a situation is perceived as unfair: for the second player, restoring equality (no one receives any money) sometimes feels more important than obtaining a reward. The ultimatum game is then used as an experimental way of measuring sensitivity to fairness.

To fully exploit this effect, the researchers recruited 101 participants. For seven weeks, 51 took dietary supplements containing probiotics (beneficial bacteria) and prebiotics (nutrients that promote the colonization of bacteria in the gut), while 50 others received a placebo. They all participated in an ultimatum game during two sessions at the beginning and end of the supplementation period.

Are bacteria pulling the strings?

The study’s results indicate that the group that received the supplements was much more inclined to reject unequal offers at the end of the seven weeks, even when the money split was slightly unbalanced. Conversely, the placebo group behaved similarly during the first and second test sessions.

Moreover, the behavioral change in the supplemented group was accompanied by biological changes: the participants who, at the start of the study, had the greatest imbalance between the two types of bacteria that dominate the gut flora (Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes) experienced the most significant change in the composition of their gut microbiota with the intake of supplements. In addition, they also showed the greatest sensitivity to fairness during the tests.

The researchers also observed a sharp drop in their levels of tyrosine, a dopamine precursor, after the seven-week intervention. For the first time, a causal mechanism is emerging: the composition of the gut microbiota could influence social behavior through the precursors of dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in brain reward mechanisms.

“It’s too early to say that gut bacteria can make us less rational and more receptive to social considerations,” concludes Plassmann. “However, these new results clarify which biological pathways we must look at. The prospect of modulating the gut microbiota through diet to positively influence decision-making is fascinating. We need to explore this avenue very carefully.”

Leave a Reply