A rapid surge in coronavirus cases saw South Korea become one of the world’s worst-affected countries outside China, but it has since cut infection rates significantly and has one of the lowest fatality rates anywhere.

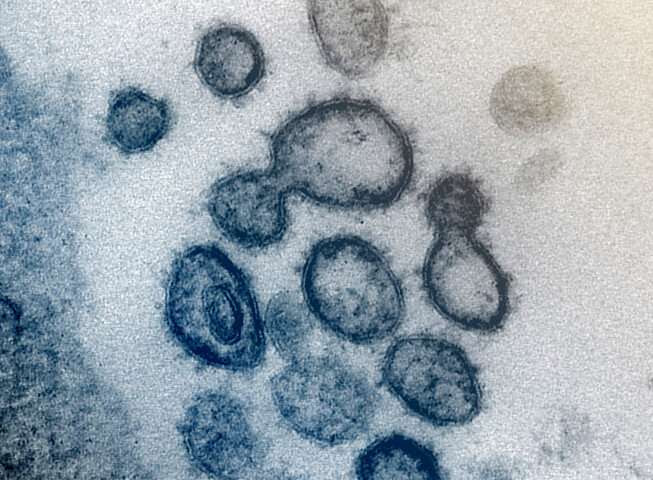

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 — also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19 — isolated from a patient in the US. Virus particles are shown emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles give coronaviruses their name, crown-like. Credit: NIAID-RML

As of Wednesday, it had 7,755 confirmed cases—the fourth-highest total in the world—but only 60 deaths, well below the World Health Organisation’s global average.

What has South Korea done and can it set an example? AFP takes a look.

How has South Korea handled the epidemic?

Instead of taking the Chinese approach of locking down affected cities, South Korea has embraced a model of open information, public participation and widespread testing.

Each confirmed coronavirus patient’s contacts are traced and offered tests.

The infected person’s movements over the preceeding 14 days—determined through credit card use, CCTV footage and mobile phone tracking—are also posted on government websites, with text message alerts sent to people when a new infection emerges in the area where they live or work.

The tactic has raised privacy concerns, but enables people to come forward for checks.

Testing fees are around 160,000 won (US$134), but free for suspected patients—people linked to confirmed cases—or those who test positive, encouraging participation.

That helps with early detection and tackling the spread of infection.

South Korea has conducted more diagnostic tests faster than any other country—around 10,000 per day—which specialists say has helped the country with early detection of patients and tackling the infection’s epicentre.

How has it tested so many people?

South Korea can carry out more than 15,000 diagnostic tests a day, and had conducted 220,000 as of Wednesday. It has more than 500 designated testing clinics, including over 40 drive-through facilities that minimise contact between patients and medical workers.

The South has had the benefit of experience: it struggled with a lack of testing kits during the 2015 outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), prompting it to create a system to expedite approvals.

Within weeks of the outbreak emerging in China, newly-developed COVID-19 testing kits which show results in just six hours received emergency government approval and were made available for clinics.

How have people reacted to government instructions?

Authorities have urged people to stay indoors, avoid meetings and minimise contact with others, in a so-called “social distancing” campaign, resulting in quiet streets and half-empty stores and restaurants, even in normally busy parts of Seoul.

Scores of events—from K-pop concerts and sports games—have been cancelled and most people wear masks, according to government recommendations.

The South is a democracy but also has a disciplined civil society, something analysts point to as a factor: “In democracies, we often are a little dismissive of whichever government is in power and take their advice with a grain of salt,” said Marylouise McLaws of the University of New South Wales, an epidemiologist and advisor to the World Health Organisation.

Why is the death rate so low?

Several factors are behind the South’s unusually low death rate—0.77 percent against a global average of 3.4 percent. Early detection enables early treatment, and widespread testing means mild or asymptomatic cases are more likely to be identified, driving up the total number of cases so the proportion dying goes down.

In addition, the infected population in the South has a unique profile: most of the country’s infections are in women, and nearly half are in people aged below 40.

Officials say that is driven by the fact that more than 60 percent of its cases are linked to the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, a secretive religious group often condemned as a cult.

Most of its members are women and many are in their 20s and 30s.

But global figures show the virus is most deadly among older generations, and men in particular.

Should South Korea be seen as an example?

Japan—where nearly 600 people have been infected, with 12 deaths—has not undertaken widespread testing and could learn from South Korea’s response, said Masahiro Kami, head of the Tokyo-based Medical Governance Research Institute.

“Testing is a crucial initial step to control the virus,” Kami said, adding: “It’s a good model for every country.”

South Korea had “gone in hard and fast”, said McLaws of the University of New South Wales, contrasting its approach with that of Italy, where she said the outbreak could have taken a different course if containment measures had been imposed earlier.

“It’s very hard for the authorities—the government—to take the plunge in doing that. So it’s often done late.”

Leave a Reply