September 17, 2024

by Amsterdam University Medical Centers

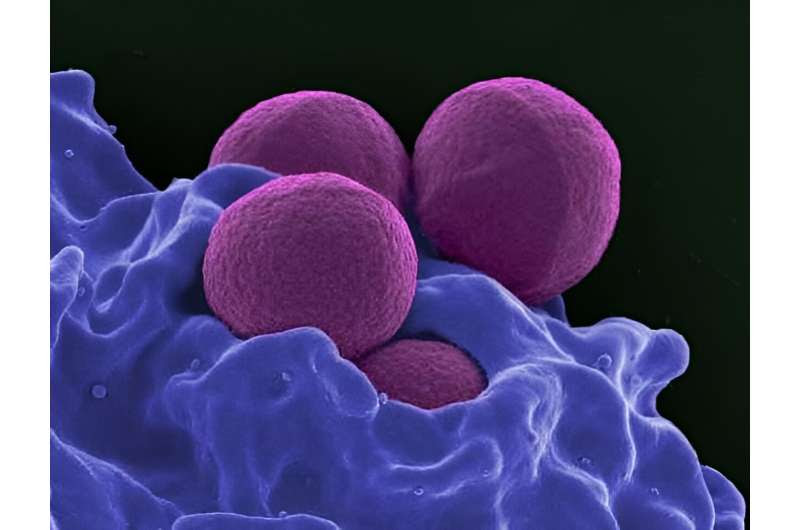

A colorized scanning electron micrograph of MRSA. Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Staphylococcus aureus, mostly known from its antibiotic-resistant variant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), is among the leading causes of both community- and hospital-acquired infections. According to the most recent data, MRSA killed around 120,000 people in 2022 globally and far more are killed by antibiotic-susceptible strains of S. aureus.

So far, however, all attempts at developing a protective vaccine for S. aureus have been unsuccessful. Research from Amsterdam UMC, in collaboration with UMC Utrecht, Leiden University, and the University of California, San Diego, have discovered an important immune component that offers protection against infection, suggesting a new direction for the future. These results are published in Cell Reports Medicine.

“Our findings directly challenge the current way of thinking about staphylococcal infections. It is generally assumed that the recognition of S. aureus by IgG antibodies, which helps immune cells to kill Staph, is key to offering protection. In this study we propose that this might not be the answer. We show that not IgG, but IgM antibodies are required for clearance of S. aureus during an infection,” says Nina van Sorge, professor of Translational Microbiology at Amsterdam UMC.

The research team, led by prof. van Sorge and Dr. Astrid Hendriks, a postdoc in her group, explored the presence of S. aureus-recognizing antibodies in the blood of healthy individuals. They focused on particular sugars, which form a sort of sugar coat around the bacterium. They found that almost all healthy individuals had both IgG and IgM antibodies that could recognize these sugar coats.

“We all have high antibody levels against the S. aureus sugar coat, since we are exposed to this bacterium multiple times throughout our lives without getting ill. Yet we don’t know which antibodies are in fact preventing us from getting ill,” says Hendriks.

In the lab, IgM antibodies were significantly more effective at killing the bacteria than IgG.

“IgG antibodies offer protection against bacterial pathogens in general and are actually critical for the protective effect of vaccines against, for example, pneumococcal and meningococcal infections. But for S. aureus, it is more complex. This clever bacterium has developed ways to circumvent our defense system, and in particular IgG antibodies, which is part of the reason that it still causes so many problems,” says van Sorge.

However, researchers found that S. aureus did not counter the effects of IgM.

Finally, they discovered that patients with life-threatening S. aureus bloodstream infections actually had much lower levels of sugar coat-specific IgM antibodies in their blood than healthy individuals. Importantly, patients that did not survive the infection had the lowest amount of IgM antibodies.

The researchers hypothesize that insufficient levels of sugar-specific IgM antibodies increase the risk of serious staphylococcal infections, and even mortality.

Although more research is needed to validate this hypothesis, these findings provide important new insights that may shape future development of vaccines and other immune-boosting therapies.

More information: Glycan-specific IgM is critical for human immunity to Staphyloccus aureus, Cell Reports Medicine (2024). On bioRxiv: www.biorxiv.org/content/10.110 … /2023.07.14.548956v2

Journal information: Cell Reports Medicine , bioRxiv

Provided by Amsterdam University Medical Centers

Leave a Reply