As deadly heatwaves become more common, researchers are studying what people can tolerate.

People have struggled to keep cool during intense heatwaves in this year’s Northern Hemisphere summer. Credit: Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty

This year’s Northern Hemisphere summer has been unlike any other. In July in Mexicali, northern Mexico, temperatures reached a blistering 47 °C, forcing people to remain inside to avoid dizziness and fainting. Across Mexico, a heatwave in June and July killed at least 167 people. In July, a weather station in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region logged 52.2 °C; California’s Death Valley saw a punishing 53.3 °C. And in August, at Iran’s Qeshm Dayrestan airport, high temperatures and humidity combined to create conditions that would kill healthy people in only a few hours.

These are just a few examples of the intense heatwaves that have featured in this year’s Northern Hemisphere summer, which has been the hottest on record by a large margin. Although the summer months have now ended, extreme heatwaves and their effects on people are likely to be a challenge worldwide for decades to come. Such heat events will become more common and more severe with climate change, say researchers, raising concerns about what the human body can ultimately tolerate — and whether societies can adapt.

“What we’re seeing very clearly is that heat is affecting health directly,” says Marina Romanello, a climate and health researcher at University College London. “The increased incidence of very extreme heat is linked to an increased morbidity and mortality.”

“There are few doubts that we will continue seeing hotter summers, and more frequent and intense, and longer, heatwaves with global warming,” says environmental epidemiologist Josep Antó at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health in Spain.

Kidney dysfunction

This year, a strong El Niño ocean-warming event is helping Earth to shatter temperature records. But climate scientists have calculated that heat events in July in Europe and the United States would have been almost impossible without global warming, and climate change made China’s heatwave 50 times more likely.

Some places might still occasionally see colder spells and milder summers owing to yearly variation, says Colin Raymond, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. But the overall warming trend will lead to heatwaves that push human limits, and expose people to health dangers. The effects of heat on the body are well known: it strains the heart and kidneys, causes headaches, disrupts sleep and slows cognition. In extreme cases, heat stroke can lead to multi-organ failure (see ‘Taking the heat’). “Heat stroke is a medical emergency. It is lethal,” says Romanello.

Taking the heat

When the human body is exposed to high temperatures, organs struggle to perform their essential tasks. Long-term exposure can cause chronic disease.

Brain

Heat causes dizziness and fainting if the body is dehydrated. It can also disrupt sleep, which reduces a person’s ability to focus and learn.

Heart

As the body warms, blood vessels dilate, lowering blood pressure. The heart pumps harder and faster to maintain consciousness, which can cause heart attacks in people with cardiovascular disease.

Lungs

Hot air aggravates respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, causing breathing difficulties.

Kidneys

Dehydration lowers blood pressure, which can limit blood flow to the kidneys. This can cut their oxygen supply, causing damage. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat can lead to chronic kidney disease.

Heat’s effect on the kidneys could contribute to the high rates of unexplained chronic kidney disease among young agricultural workers in countries including El Salvador, India and Pakistan, says Ollie Jay, a physiologist at the University of Sydney, Australia.

These workers “are spending hours in the heat, often with little access to water”, says public-health researcher Dileep Mavalankar at the Indian Institute of Public Health Gandhinagar. A 2021 study1 in India found a 1.4-fold increase in risk of kidney dysfunction among outdoor workers including those in agriculture and construction, compared with people doing physical jobs indoors.

Heatwaves are especially dangerous to vulnerable people — including older people, newborns and those with underlying conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. Children less than one year old struggle to cope because their thermoregulation system isn’t fully developed, says Mavalankar. And older people, particularly those over 75, struggle to cool themselves down because their sweat glands become less sensitive to the brain’s chemical signals, says Jay.

Climate change made North America’s deadly heatwave 150 times more likely

A heating planet will mean increases in mortality and in rates of respiratory and heart disease, says Antó. It could also increase the number of suicides2, and rates of premature birth and low birth weight are expected to grow, because heat reduces blood flow through the placenta and so interrupts the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, he says. This will undoubtedly strain health systems, he adds.

In July, the hottest regions of the United States, including California, Arizona and Nevada, saw increased rates of heat-related illness among people visiting hospitals, compared with cooler states. Spain saw heat-related deaths surge in July and August. “Heat is a silent killer that sneaks up on people,” says Kristie Ebi, who studies the health impacts of climate change at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Humid heat

Researchers are seeking to understand the limits of what the human body can handle. There is no generally accepted temperature threshold, in part because heat affects people differently depending on conditions such as humidity.

Temperatures given in weather reports are typically dry air temperatures taken by ordinary thermometers, which do not reflect other factors that can affect the body. To consider effects such as humidity, scientists use a measure called the wet-bulb temperature. This accounts for the fact that sweat evaporates less easily when the air is saturated with water, says Jay.

Researchers have estimated3 that a critical wet-bulb temperature for people is 35 °C. At this threshold, a healthy person can survive for only around six hours, because no heat is lost from the body through sweating or radiation, leading to heat stroke in even the healthiest people. “Everyone will die at that point,” says Jay.

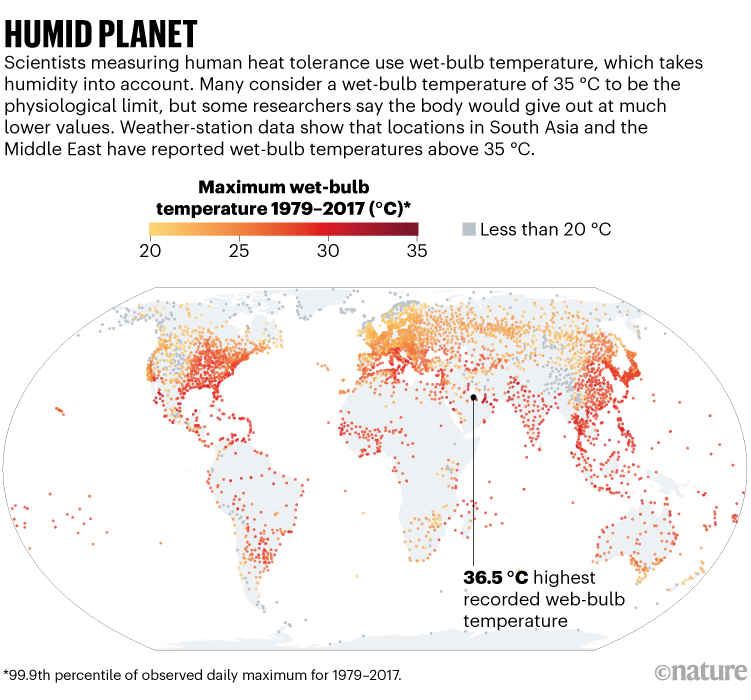

Wet-bulb temperatures are highest in subtropical, coastal locations in South Asia, the Middle East and southwestern North America, where there is a potent mix of heat and humidity (see ‘Humid planet’).

An analysis4 of weather-station data dating back to 1979 shows that wet-bulb temperatures in Pakistan and the Gulf have breached the 35 °C threshold for one or two hours at a time on several occasions, mostly since 2003.

Humid planet: World map showing the locations of weather stations that have reported web-bulb temperatures nearing 35 °C.

Source: Ref 4.

On 6 July, the world’s hottest day ever, wet-bulb temperatures reached up to 27 °C in southern European countries including Spain and Italy.

But the estimated limit of 35 °C is imperfect, says Jay: the body would probably give out at a much lower temperature. This limit was defined by computational models that treat the body as an object without accounting for some physiological factors, such as how much sweat people can actually produce, he says. “In hot and very dry environments, you wouldn’t be able to survive way below the 35 °C wet-bulb limit, because you wouldn’t be able to produce enough sweat,” says Jay. These models also assume that a person is completely sedentary and so not producing heat from movement. A more useful limit would account for a person carrying out some tasks, says Jay.

View of Freetown, Sierra Leone.

In Freetown, Sierra Leone, a tree-planting scheme is one of the efforts to provide shade to shield people from severe heat.Credit: Abenaa/Getty

Jay’s team is looking to define a more accurate limit for human survivability that considers these factors. “We’re then going to validate that model in human participants using the climate chamber,” says Jay. The chamber, at the University of Sydney in Australia, allows the team to measure a participant’s heart strain and kidney function while turning up heat and humidity until body temperatures hit 39.5 °C. Using these data, the researchers will predict how various conditions induce the development of heat stroke, says Jay. “We can extrapolate those bodily changes at sub-critical core temperatures to critical limits,” he says.

Jay also plans to determine the most effective ways to cope with extreme heat. Most recommendations for protection methods are based on laboratory studies conducted in highly controlled conditions, he says. “The next step is to test these interventions in real-world heatwaves.” His team hopes to conduct such a study in people in India during the hot season, and the researchers are developing wearable devices that will monitor dehydration, kidney function, blood pressure and heart rates.

How to adapt

While researchers investigate the body’s limits and the best ways to adapt, countries and cities are making a slew of efforts to shield people from severe heat. “It’s becoming a do or die situation,” says Eugenia Kargbo, chief heat officer for Freetown in Sierra Leone, a post created by the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, part of the Atlantic Council policy institute in Washington, DC.

Elegant adobe-style homes beneath the towering gaze of the nearby Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Narrow, white buildings in cities such as Dubai (pictured) are designed to reflect and keep out heat.Credit: Tyson Paul/Loop Images/Universal Images Group via Getty

In rich regions, often in the global north, air conditioning is perhaps the most effective strategy for cooling people down. But this requires electricity, producing planet-heating greenhouse gases by burning fossil fuels, Jay says. What’s more, because human bodies can adapt to higher temperatures to some extent through exposure, air conditioning might even reduce people’s capacity to cope without it, says Ebi.

More sustainable strategies might prove more fruitful in the long-term. Dousing the skin with water using a spray bottle or sponge and immersing the feet in cold water are cheap and easy ways to lower the body’s temperature. Electric fans use as little as one-fiftieth the electricity of air conditioning for the same amount of cooling. In Japan, an energy-saving campaign encourages a simple change: swapping heavy business wear for cooler, lighter clothing.

Cities must protect people from extreme heat

Adapting the environment can also help. In Freetown, Kargbo and other local residents have planted 750,000 trees; trees can cool cities by providing shade and releasing water vapour. Kargbo has also helped to put reflective covers on market stalls to shade fruit and vegetables traders.

In countries including India, France, the United Kingdom and Spain, early-warning mechanisms alert health-care systems and the public to hot days ahead. When it was trialled in Ahmedabad, India, an early-warning system led to a 30–40% decrease in mortality during heatwaves, says Mavalankar. Many cities and states across India have now implemented the strategy.

Still, poor regions, many in the global south, face challenges. “One of these is a huge lack of health-care data on both disease rates and mortality,” says Mavalankar.

“This makes it hard to quantify how well heat-adaptation approaches are working,” says Kargbo.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02482-z

Additional reporting by Layal Liverpool.

References

Venugopal, V., Shanmugam, R. & Kamalakkannan, L. P. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 085008 (2021).

Burke, M. et al. Nature Clim. Change 8, 723–729 (2018).

Sherwood, S. C. & Huber, M. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 107, 9552–9555 (2010).

Raymond, C., Matthews, T. & Horton, R. M. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw1838 (2020).

Leave a Reply