- Over two percent of the population develops obsessive-compulsive disorder at some point over the course of their lives

- Repetitive thoughts, compulsions, and behaviors can disrupt these peoples’ lives and isolate them

- OCD is characterized by an overly-active brain circuit

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation uses magnetic pulses to disrupt the electrical activity in this circuit

- A similar treatment from Brainsway (and other manufacturers) was already approved to treat depression

A brain ‘zapping’ device was approved to treat the obsessive-compulsive disorder by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has already been approved and incorporated as a novel treatment option for a range of neurological and mental health disorders, including depression, Parkinson’s, PTSD and schizophrenia.

Magnets in a helmet deliver a series of short, low-powered pulses to the brain, interfering with its own electrical communication system.

The method of disrupting the brain’s communication circuitry is thought to help open up the mental ‘loop’ of an OCD-sufferer’s repetitive thinking.

A hi-tech helmet sends magnetic pulses deep into the brain in order to disrupt the overly-active circuit of electrical signals that lead to obsessive-compulsive behaviors

OCD is far more common – and describes a wider range of issues – than you might think.

More than two percent of the American population will deal with a form of the disorder at some point in their lives.

Anyone who is having repetitive, intrusive thoughts about a topic or behavior that they seem to get stuck on could have diagnosable OCD.

Common OCD fixations include death, sex, hand-washing or cleanliness, possessions (which may lead to hoarding), plucking at hair or skin, and counting.

Compulsions primarily develop out of anxieties. The specific behaviors somehow get mentally linked to relief from these stressors and become habitual and even obsessive.

Essentially, the brain develops an overly-active circuit of responses, and this is what clinicians seek to tone down.

For some, these compulsions will subside with cognitive behavioral therapy to retrain the brain out of fixation.

Others require medication, like an antidepressant or an anti-anxiety drug like Paxil.

But even with medication, therapy, or a combination of the two, some find only minimal relief from intrusive obsessions that can lead to social isolation and debilitating fixation.

OCD patients’ brains show ‘hyper-synchronicity,’ meaning there is ‘an increased amount of simultaneous firing’ in this circuit of responses, explains Dr. Aron Tendler, the chief medical officer for Brainsway.

That’s what his company’s device has now been approved to disrupt.

‘The brain has a lot of chaos normally, and for people with OCD, they have all these regions firing at once,’ he says.

‘We want to mess with the pathological rhythms in the circuit to normalize the whole circuit.’

Brainsway’s TMS device does this by sending a series of magnetic pulses into a region of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex.

This area acts like an operator, connecting the emotional sections of the brain to the cognitive ones. It isn’t the only area of the brain involved in OCD’s complex circuit, but it is an important one.

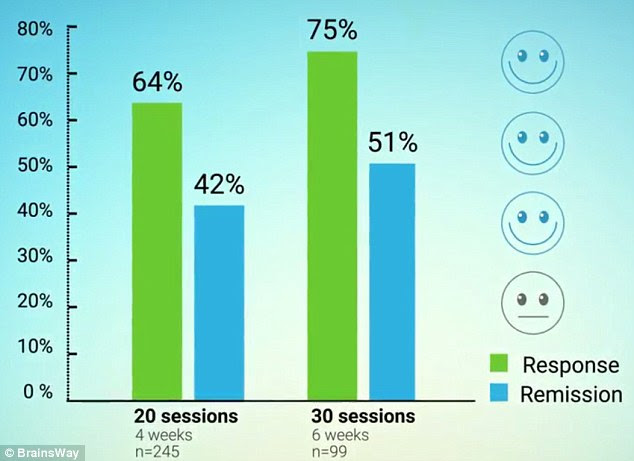

About half of the patients that Brainsway tested their TMS device on saw significant and lasting improvements after 30 sessions, and 75 percent felt some improvement

Since brain regions talk to one another through electrical signals, TMS blasts brief magnetic fields into this communication hub, disrupting the circuit.

The technology is similar to Brainsway’s device for treating depression but is wired quite differently in order to target the anterior cinguate cortex, deep within the brain.

First, a clinician works out the ‘dose’ by targeting different, but a similarly deep section of the brain that, when properly poked, makes the foot kick.

Once it’s clear how strong the pulses need to be, the clinician has to provoke the patient’s compulsions, perhaps by saying that the device hasn’t been cleaned and is covered in germs, and has the patient rate their obsessive feelings at that moment.

If the patient is ‘moderately’ obsessive, it’s time to break the circuit.

The device – coils and wires nestled in a helmet that resembles a salon hair dryer – is moved over the anterior cingulate cortex. There, it fires 2,000 pulses that last about two seconds each, over the course of 18.3 minutes.

It’s a pretty painless procedure – Dr. Tendler says it feels like ‘tapping’ on the head – but it has to be repeated 30 times, usually over the course of six weeks, and some patients walked away with headaches.

In their trial with 100 people, he and his team saw that those who got the real treatment felt markedly more improvements than those who were given a sham.

About 75 percent felt some improvement after the treatment, and about 50 percent felt a significant improvement.

And, for at least the month after treatment that Brainsway followed up with the study participants, the effects were ‘sustained, and didn’t go away, so we generated some neuroplasticity,’ says Dr. Tendler.

It isn’t clear yet if the benefits might last any longer than that or how much variation there might need to be in repeat treatments.

Brainsway’s previous device was approved by the FDA and is covered by ‘all’ insurers to be used for treatment-resistant depression, at a cost of $5,000 to $10,000 for four to six weeks of treatment.

Dr. Tendler said he doesn’t know what the total cost – covering the clinician’s fees, overhead and any time in the hospital, as well as the device – will be, but says that Brainsway will make the same ‘nominal’ amount from the device.

But patients will still have to try traditional therapies first, without complete success, in order to try the device, according to the FDA.

Leave a Reply