by University of Michigan

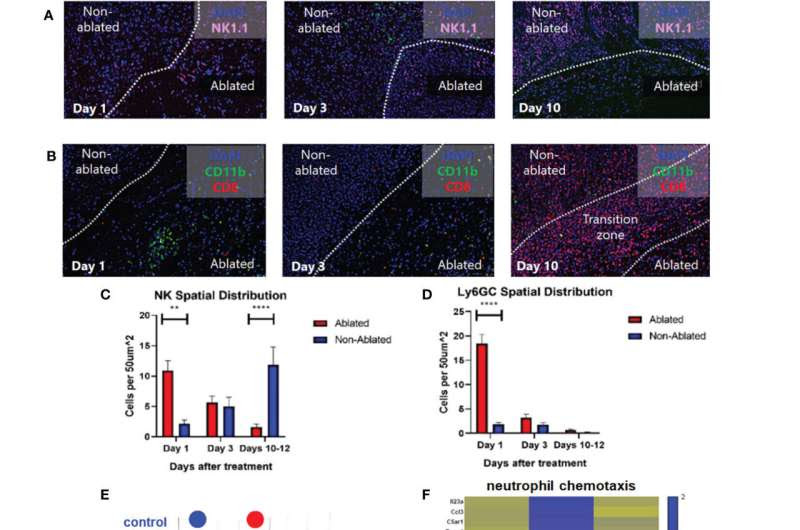

Histotripsy ablation is followed by infiltration of innate and adaptive immune cell populations. Mice bearing bilateral B16F10 tumors were treated with unilateral sham (control) or partial histotripsy ablation on day 10. Multicolor immunofluorescence performed 1, 3 and 10 days after sham or histotripsy partial histotripsy ablation revealed (A) early infiltration of NK1.1+ cells initially localized within the histotripsy ablated zone that gradually migrated outward toward peripheral, non-ablated zones on days 3 and 10, and (B) early and transient infiltration of CD11b+ cells within the histotripsy ablated zone on day 1 and delayed infiltration of CD8+ T cells within the non-ablated zone on day 10. (C) Quantitation of NK1.1+ cells within ablated zones (red) and non-ablated zones (blue) of histotripsy-treated tumors at various time points revealed gradual migration of NK cells away from ablated zones toward non-ablated zones. (D) Quantitation of Ly6GC+ cells at various time points after histotripsy confirmed immediate but short-lived infiltration strictly localized to the ablated zone. (E) RNASeq of CD45+ immune cells performed 3 days after unilateral partial histotripsy ablation revealed marked differences in transcriptional activity between control tumors (blue) and histotripsy-treated (“HT-Tx”) tumors (red) as evidenced by principal component analysis. (F) Upregulated transcription of genes associated with neutrophil chemotaxis was observed in histotripsy-treated but not histotripsy-abscopal (“HT-Abs”) tumors. (G) Mice bearing bilateral Hepa1-6 tumors were treated with unilateral partial histotripsy ablation on day 10. Flow cytometric analysis of tumor-draining lymph nodes of control (blue), histotripsy-treated (green) and histotripsy-abscopal (red) tumors performed on day 13 revealed significant increases in cDC1 and cDC2 populations within lymph nodes draining histotripsy-treated tumors. (H) Similarly, flow cytometric analysis revealed significant increases in activated CD8+ T cells within lymph nodes draining histotripsy-treated tumors. (n=3-6 mice per group; *=p<0.05 between groups; **=p < 0.01 between groups; ****=p < 0.0001 between groups). Credit: Frontiers in Immunology (2023). DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1012799

When non-invasive sound waves break apart tumors, they trigger an immune response in mice. By breaking down the cell wall “cloak,” the treatment exposes cancer cell markers that had previously been hidden from the body’s defenses, researchers at the University of Michigan have shown.

The technique developed at Michigan, known as histotripsy, offers a two-prong approach to attacking cancers: the physical destruction of tumors via sound waves and the kickstarting of the body’s immune response. It could potentially offer medical professionals a treatment option for patients without the harmful side effects of radiation and chemotherapy.

Until now, researchers didn’t understand how histotripsy activated the immune system. A study from last spring showed that histotripsy breaks down liver tumors in rats, leading to the complete disappearance of the tumor even when sound waves are applied to only 50% to 75% of the mass. The immune response also prevented further spread, with no evidence of recurrence or metastases in more than 80% of the animals.

“We found that histotripsy somehow not only kills cancer cells, but causes them to undergo a unique pathway of cell death that draws the attention of the immune system,” said Clifford Cho, the C. Gardner Child Professor of Surgery and vice chair of surgery, whose lab designed immune study protocols and measured immune responses for the study published this month in Frontiers in Immunology.

The key turned out to be tumor antigens—proteins only found in cancer cells and hidden behind their cell walls. When cells die by chemotherapy or radiation, these antigens are destroyed in the process. In contrast, sound waves kill the cancer cells by breaking their cell walls, releasing tumor antigens that then trigger the body’s defense systems.

The immune response occurred throughout the body, not simply in the area where the histotripsy was applied.

“With histotripsy, we’re not destroying the antigens, we’re releasing them while killing the tumor cells,” said Zhen Xu, U-M professor of biomedical engineering and an inventor of the histotripsy approach. “Once they’re no longer hidden, the body can see them and attack them.”

The team was able to discover the mechanism due to the way mice in cancer studies are typically given genetically identical tumors. After breaking up a tumor in one mouse using histotripsy, the team extracted some of that material, homogenized it and injected it into another mouse. Both mice developed immune protection from that cancer.

“Injecting the debris into a second mouse had almost a vaccine-like property,” Xu said. “Mice that received this debris were surprisingly resistant to the growth of cancers.”

Since 2001, Xu’s laboratory at the University of Michigan has pioneered the use of histotripsy in the fight against cancer, leading to the multi-center clinical trial #HOPE4LIVER. More recently, the group’s research has produced promising results on histotripsy treatment of brain cancer therapy and immunotherapy.

Leave a Reply