by University of Freiburg

T cells play a huge role in our immune system’s fight against modified cells in the body that can develop into cancer. Phagocytes and B cells identify changes in these cells and activate the T cells, which then start a full-blown program of destruction. This functions well in many cases—unless the cancer cells mutate and develop a kind of camouflage that let them escape the immune system undetected.

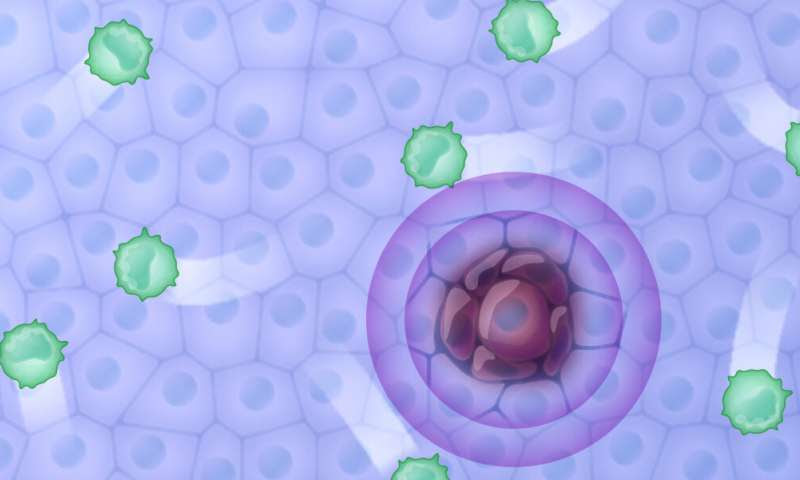

Cancer cells become invisible to the body’s immune response. Unhindered by T cells (green), they can continue to replicate. Scientists have now described an important step in this process called “immune escape”. Credit: CIBSS/University of Freiburg, Michal Roessler

Researchers at the University of Freiburg and the Leibniz University Hannover (LUH) have now described how a key protein in this process, known as “immune escape,” becomes activated. The team, headed by Prof. Dr. Maja Banks-Köhn and Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schamel at the University of Freiburg and structural biologist Prof. Dr. Teresa Carlomagno from the LUH, used biophysical, biochemical and immunological methods in their research. Based on these insights, Banks-Köhn hopes to develop drugs that intervene specifically in this activation mechanism. In the future, they could improve established cancer treatments that rely on so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors. The team has recently published its research in Science Advances.

Checkpoint inhibitors are therapeutic antibodies that work by binding to the receptors of T cells. There are proteins on the surface of the T cells called immune checkpoint receptors, which include programmed cell death 1, or PD1, along with the signaling pathways triggered by these proteins. Together, these stop immune responses in a healthy body. This regulating mechanism prevents symptoms of inflammation from lasting too long and getting out of control—symptoms of uninhibited inflammation include redness, swelling and fever.

Cancer cells take advantage of inflammation mechanisms to render the body helpless while the cells multiply. Using cell cultures and interaction studies, the researchers from the two universities discovered that a signaling protein called SHP2 in T cells binds to PD1 in two specific places after it has been activated by a signal from cancer cells. It is this double binding to SHP2 that promotes the camouflaging effect and switches off the immune cells’ response completely.

Antibodies that block immune inhibitors like PD1 are approved treatments for skin melanomas and lung carcinomas, and they prolong patients’ lives. However, as a result, many patients suffer from autoimmune reactions. “Drugs that prevent the binding of SHP2 and PD1 could be used in the future to make side-effects less severe and to support, or act as alternatives to, antibody treatments,” says Banks-Köhn.

She and Schamel studied the immune response of B cells and T cells by modifying SHP2 molecules, testing their predictions based crystal structure and magnetic resonance analysis of the team from the LUH. Their data shows precisely how and in what areas the SHP2 protein binds to PD1, thereby revealing a possible target area for drugs. “In our ongoing research project, the next step is to decode the signaling pathway of PD1—in other words, where the proteins are located in the cell, where they bind, and within what time frame the signals take effect,” Banks-Köhn says.

Leave a Reply