This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson, coming at you once again from isolation. Please excuse the webcam.

Coronavirus has caused us to reevaluate so many things. I’m doing renal consults today from my office, only physically going to see patients if absolutely necessary—something unthinkable just a few weeks ago. It’s also causing us to reevaluate what we mean by “evidenced-based medicine.” In the days before the pandemic, many of us were of the “randomized trial or bust” mindset, often dismissing good observational studies without rigorous review, and likewise embracing even suspect studies just because they happened to be randomized.

But with the novel coronavirus, we don’t have the luxury of waiting for those big, definitive randomized trials. We need to act on the data we have. We need to remember what evidenced-based medicine is really about. It’s not just randomized trials; it’s integrating each study into the body of existing data, combining the best available science, reaching defensible conclusions.

I like to read a new study in the context of what I call “the pre-study probability of success.” In other words, how likely was this drug to work before we got the data from the trial? Let me show you how this works with two recent examples.

I’m going to start with the big one.

It seems like everyone is talking about hydroxychloroquine, thanks to one little study appearing in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents that is generating a lot of press—thanks to a shout-out from Donald Trump, no less.

What is our pre-study probability that hydroxychloroquine would be effective for COVID-19?

There’s a lot of literature here. Hydroxychloroquine has a long history as an antibiotic and antiviral drug and, encouragingly, seems to inhibit coronavirus replication in vitro. It also changes the structure of the receptor that coronavirus binds to.

I’d put the pre-study probability here at around 50/50, but feel free to disagree.

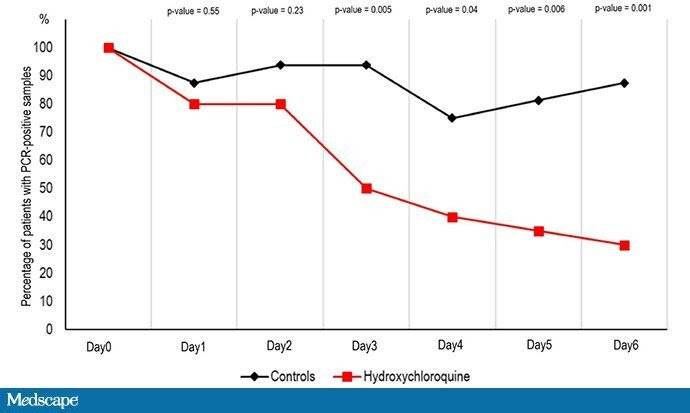

Now let’s look at the study. Thirty-six patients in France with COVID-19 were examined. Twenty of them got hydroxychloroquine and 16 were controls. But this was not randomized; treated patients were different from those not receiving treatment. The researchers looked at viral carriage over time in the two groups and found what you see here:

This appears to be a dramatic reduction in coronavirus carriage in those treated with hydroxychloroquine. Awesome, right? Sure, it’s not randomized, but when we need to make decisions fast, “perfect” may be the enemy of “good.” Does this study increase my 50/50 prediction that hydroxychloroquine could help?

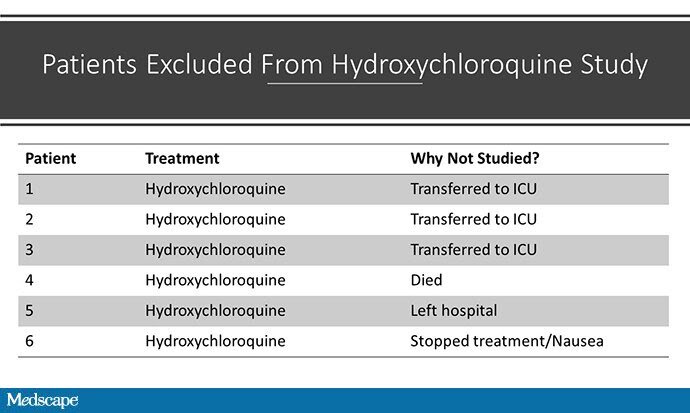

Well, with data coming at us so fast, we have to be careful. There is a huge fly in the ointment in this study that seems to have been broadly overlooked, or at least underplayed. There was differential loss to follow-up in the two arms of the study; viral positivity was not available for six patients in the treatment group, none in the control group. Why unavailable? I made this table to show you:

Three patients were transferred to the ICU, one died, and the other two stopped their treatment. By the way, none of the patients in the control group died or went to the ICU. Had these six patients not been dropped, the story we might have is that hydroxychloroquine increases the rate of death and ICU transfer in COVID-19.

Before reading this study, I was 50/50 on hydroxychloroquine. After?

Yeah, I’m right where I started. Because of the problems with the study design—not just its observational nature but that differential loss to follow-up—the data from the French study don’t move the needle for me at all.

That doesn’t mean hydroxychloroquine failed.

What we have to decide now is whether 50/50 is good enough to try. Given the relatively good safety profile of hydroxychloroquine and the dire situation we find ourselves in, it may be very reasonable to use this drug, even despite that study.

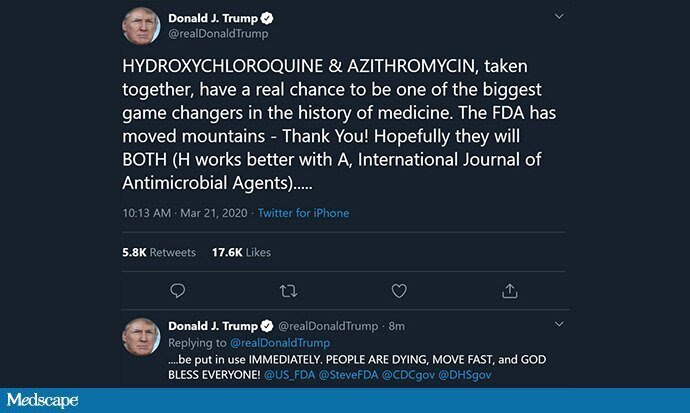

Tweets like this, though, aren’t helpful:

They misrepresent the data, which are equivocal at best. Further, they may encourage people to think, we’ve solved this, and stop their social distancing. There are already reports of these medicines being hoarded. The key to evidence-based medicine during this epidemic is being transparent about what we know and what we don’t. If we want to use hydroxychloroquine, that is a reasonable choice, but we need to tell the public the truth: We’re not too sure it will work, and it may even be harmful.

The second example I wanted to share is this randomized trial evaluating lopinavir-ritonavir for adults with severe COVID-19.

Before I read this trial, did I think lopinavir would work for COVID-19? For a nephrologist like me, this requires a bit of reading, but there were some studies showing that the drug inhibited viral replication in vitro and some data suggesting that it may have had some effect treating SARS during that epidemic.

But overall, I pegged the pre-study probability of success to be fairly low—let’s give it 10%. Experts can differ with me. I won’t be offended.

That said, this was a nice randomized trial in 199 people with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The 28-day mortality was 19.2% in the treatment group and 25.0% in the placebo group. That seems good, but it wasn’t statistically significant; the P value was 0.32.

In ordinary days, we’d call this nonsignificant and move on. Indeed, the authors of the manuscript write: “No benefit was observed with lopinavir-ritonavir treatment beyond standard care.”

But these are not ordinary days.

Shall we be slavishly beholden to statistical significance, even in this time of crisis? The truth is, we don’t have to compromise our principles here. One nice feature of a randomized trial is that we can use the observed P value, with some minor mathematical jiggerings, as a measure of the strength of evidence that lopinavir is effective.

This is Bayesianism, and it may be just what we need right now.

Instead of dogmatically looking for a P value below some threshold, we use the evidence in a given trial to lend support to a hypothesis that depends on our pre-trial probability that the drug being tested was effective.

Here’s a graph showing the probability that a drug is effective, after a trial reports a P value of .05, as a function of the probability that it was effective before the trial:

If you were 50/50 that the drug would work before the trial, after that P =.05, you’d be up to around 75% sure that the drug works. Maybe that’s enough to start treating.

It barely moves the needle at all. If you were 90% sure that the drug combo would work before you read the article, these data are entirely consistent with that. If you were 10% sure like me, these data support that as well. In other words, this trial should not affect our enthusiasm for this drug. It should not change much of anything.

We can use these techniques to help us make sense of the rapid-fire pace of medical research coming at us. Moreover, we can use the post-trial probability of a drug as the pre-trial probability for the next study of that drug, allowing us to ratchet up the probability curve with successive trials showing similar signals, even if none of them are classically statistically significant.

As more data come in, we can revise those estimates of efficacy, iteratively and transparently.

The bottom line is that we don’t need to abandon evidence-based medicine in the face of the pandemic. We need to embrace it more than ever. But in that embrace, we need to realize what we’ve known all along: Evidence-based medicine is not just about randomized trials; it’s about appreciating the strengths and weaknesses of all data, and allowing the data to inch us closer and closer toward truth.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Program of Applied Translational Research. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @methodsmanmd and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

Leave a Reply