JUNE 6, 2024

by University of Surrey

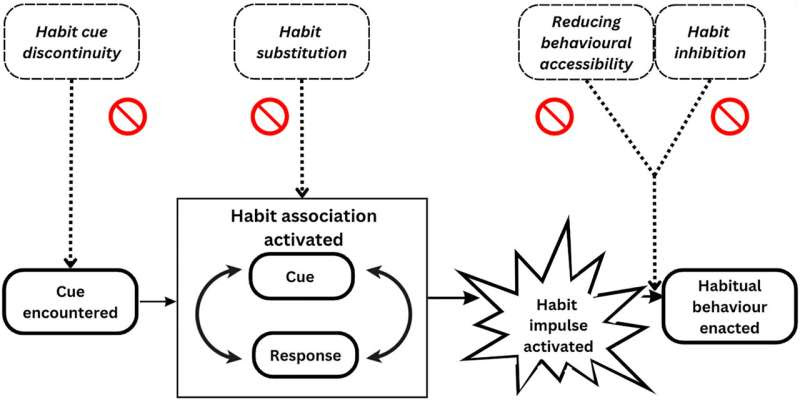

Habit disruption mechanisms, mapped to the process through which habit translates into habitual behavior. Credit: Social and Personality Psychology Compass (2024). DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12975

By ditching “pop psychology” myths about habits, we can better understand our habits and take more effective action, according to researchers at the University of Surrey.

Pop psychology tends to portray all stable behaviors as habitual, as well as implying that forming new habits will always lead to positive long-term change.

A new analysis by Surrey researchers published in Social and Personality Psychology Compass argues that a habit is simply a mental link between a situation (cue) and an action (response). When someone with a habit is in the situation, an unconscious urge prompts the action. However, whether this urge leads to habitual behavior depends on other competing impulses that influence our actions.

Dr. Benjamin Gardner, co-author and reader in psychology from the University of Surrey, said, “Forming a habit means connecting a situation you often encounter with the action you usually take. These connections help by creating impulses that push us to do the usual action without thinking. But the pushes from habits are just one of many feelings we might have at any time.

“Impulses are like babies, each crying for our attention. We can only tend to one at a time. These impulses come from various sources—intentions, plans, emotions, and habits. We act according to whichever impulse demands our attention by crying the loudest at any given moment.

“Habit impulses usually cry the loudest, guiding us to do what we normally do, even when other impulses are vying for our attention. However, there are times when other impulses cry louder.”

Other impulses can overrule your habits—like cold weather derailing your habitual morning run.

The paper points out that forming a new habit creates an association that can help keep you on the right track, but it does not ensure that a new behavior will always stick.

Dr. Phillippa Lally, co-author of the study and senior lecturer in psychology from the University of Surrey, said, “Think of someone who has developed a habit of eating a healthy breakfast every morning. One day, they wake up late, leave the house without having time for breakfast, and then grab a sugary snack on their commute.

“This single disruption can make them feel like they’ve failed, potentially leading them to abandon the healthy eating habit altogether. When trying to make a new behavior stick, it’s a good idea to form a habit and have a backup plan for dealing with setbacks, such as keeping healthy snacks on hand that you can quickly grab on busy mornings.”

As for breaking bad habits, the Surrey researchers suggest several methods.

Dr. Gardner explains, “There are multiple ways to stop yourself from acting on your habits. Imagine you want to stop snacking in front of the TV. One way is to avoid the trigger—don’t switch on the set. Another is to make it harder to act impulsively—not keeping snacks at home. Or, you could stop yourself when you feel the urge.

“While the underlying habit may remain, these strategies reduce the chances of ‘bad’ behaviors from occurring automatically.”

Dr. Lally adds, “In principle, if you can’t avoid your habit cues or make the behavior more difficult, swapping out a bad habit for a good one is the next best strategy. It’s much easier to do something than nothing, and as long as you’re consistent, the new behavior should become dominant over time, overpowering any impulses arising from your old habit.”

More information: Benjamin Gardner et al, What is habit and how can it be used to change real‐world behaviour? Narrowing the theory‐reality gap, Social and Personality Psychology Compass (2024). DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12975

Leave a Reply