by Nadine Wathen, University of Western Ontario

Being safe at home isn’t possible for everyone during this COVID-19 crisis.

It’s important rethink what we mean by “home” and “safe”—from the comings-goings of essential workers potentially exposing loved ones every time they open the front door, to the many people in our community without a front door because they lack stable housing.

Women and children living in violence are especially at risk under shelter-in-place or #StayHome directives. As stresses mount, and with no place for anyone to go, violence can escalate.

A Red Cross report shows gender-based violence—including domestic and sexual violence—generally increases after disasters. More recent anecdotal evidence coming out of places further along in the pandemic, including China, reinforce this pattern for COVID-19.

In fact, shelters and other women-serving organizations in Canada are sounding the alarm, while also trying to shift their services to ensure worker and client safety. In high-touch, compassion-centered and often emergency-based work, this is not an easy task.

As Dr. AnnaLise Trudell, Manager of Education, Training and Research at ANOVA, London’s women shelter and sexual assault service provider, says:

This is an incredibly scary time for those of us working in the violence sector. There is a feeling of impending doom. We know that we are going to see an increase in gender-based violence. We are trying to prepare for that, get our services ready, while also trying to move what services we can online and struggling with the technological adaptations.

But we also have a responsibility to employ known best practices of isolation and limiting social contact in order to keep the women and children residing our shelters as healthy and safe as possible. For many shelters, this means pausing intakes and limiting or stopping movement in and out of shelter.

This is really hard on women and their children. We’re promoting one form of safety—health—at the possible expense of another—freedom from violence. This work stress is on top of worrying about our loved ones, our finances, and our childcare while living through a pandemic.”

On March 26, the World Health Organization released a statement on violence against women and their children and COVID-19. Their key points include that many factors will interact to contribute to increased risk for women and their children, including:

Disruption to services, including sexual and reproductive health services for sexual assault survivors, and access to formal and informal support networks;

Safe shelter increasingly unavailable due to service restrictions and Canada’s ongoing housing crisis;

Increased proximity to the abuser, with no ability for respite or escape, including the potential for online activities to be closely monitored, conversations to be overheard, etc.;

Sharp increases in financial and other material stresses through job loss and underemployment;

Increased burden of child-care and other household tasks borne disproportionately by women; and

More ways for abusers to exert control, including threats of turning victims out of the home, exposing them to illness, denying access to protective supplies and spreading misinformation or stigmatizing victims.

On the bright side, we’re having these conversations.

Local, provincial and federal governments are specifically supporting domestic violence victims and others needing a safe place to stay through enhanced funding for shelters and strategies like re-purposing hotels to house those without homes.

Major media are paying attention and publishing both facts about domestic violence, and stories about what it looks and feels like for women and their children during this pandemic.

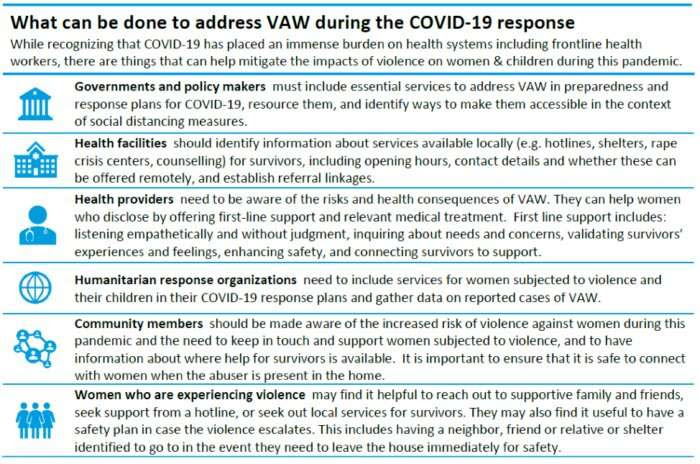

Organizations are rapidly publishing guidance for policy-makers, health and social service providers and the public about how to help, while also adapting their services to provide safety for women, children and staff.

In the WHO document cited above, the following actions are recommended:

From an information perspective, it’s also important to consider ways technology can help, but also place women at risk.

Services moving to online or phone-based platforms must account for the increased proximity of the abuser and provide enhanced safety strategies for women to cover online tracks and otherwise use safe help-seeking strategies. Helping women find useful, local and consistent information and support is also key—services such as Shelter Safe provide links to local services and supports across Canada, along with strategies to hide pages and clear search histories.

As someone who has done research in this area for more than 20 years, I am concerned about what happens when this specific crisis is over. We know that domestic femicides in Canada weren’t decreasing before COVID-19—in fact they were getting worse, as were all femicides.

Will we ensure sustained attention to addressing and preventing violence against women, homelessness and other injustices, or will we go back to being okay with a woman or girl killed in Canada every 2.5 days?

Leave a Reply