by Radiological Society of North America

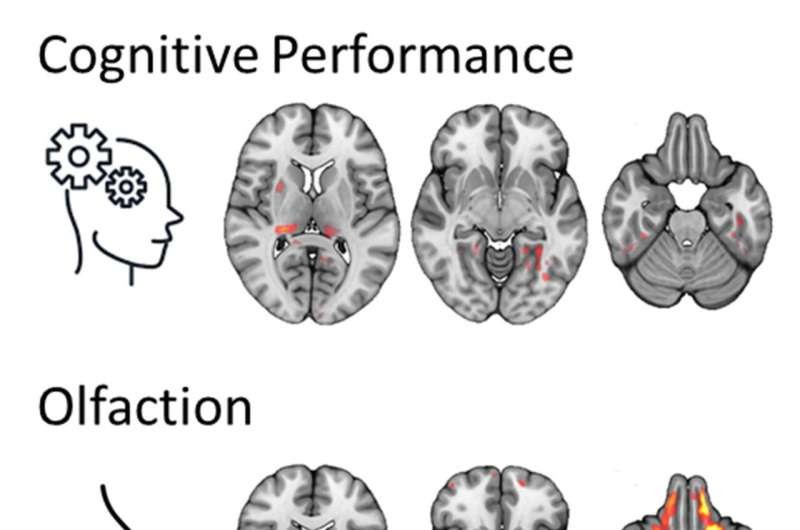

Brain regions in which the microstructure was associated with post-COVID-condition associated symptoms. Credit: RSNA/Alexander Rau, M.D.

People with long COVID exhibit patterns of changes in the brain that are different from fully recovered COVID-19 patients, according to research being presented next week at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing patients with long COVID to both a group without history of COVID-19 and a group that went through a COVID-19 infection but is subjectively unimpaired,” said one of the study’s lead authors, Alexander Rau, M.D., resident in the Departments of Neuroradiology and Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at University Hospital Freiburg in Freiburg, Germany.

After infection with COVID-19, as many as 10–25% of patients may develop a post-COVID condition commonly referred to as “long COVID.” People with long COVID may experience a wide variety of symptoms, including difficulty concentrating (“brain fog”), change in sense of smell or taste, fatigue, joint or muscle pain, shortness of breath, digestive symptoms, and more. These symptoms may persist for weeks, months, or—as is only now becoming apparent—years after COVID-19 infection.

However, the basis of this condition is poorly understood. Diffusion microstructure imaging (DMI), a novel MRI technique, is a promising approach to fill this gap.

DMI looks at the movement of water molecules in tissues. By studying how water molecules move in different directions and at various speeds, DMI can provide detailed information on the microstructure of the brain. It can detect even very small changes in the brain, not detectable with conventional MRI.

For this prospective, cross-sectional study, Dr. Rau and colleagues compared MRI brain scans of three groups: 89 patients with long COVID, 38 patients who had contracted COVID-19 but did not report any subjective long-term symptoms, and 46 healthy controls with no history of COVID-19.

The researchers first compared the cerebral macrostructure of these three groups to test for atrophy or any other abnormalities. Next, they used DMI to gain a deeper insight into the brain.

The three groups were compared to reveal group differences in the brain’s microstructure. DMI parameters were read for the gray matter in the brain. Additionally, whole-brain analyses were employed to reveal the spatial distribution of alterations and associations with clinical data, including long COVID symptoms like fatigue, cognitive impairment, or impaired sense of smell.

The results showed no brain volume loss or any other lesions that might explain the symptoms of long COVID. However, COVID-19 infection induced a specific pattern of microstructural changes in various brain regions, and this pattern differed between those who had long COVID and those who did not.

“This study allows for an in vivo insight into the impact of COVID-19 on the brain,” Dr. Rau said. “Here, we noted gray matter alterations in both patients with long COVID and those unimpaired after a COVID-19 infection. Interestingly, we not only noted widespread microstructural alterations in patients with long COVID but also in those unimpaired after having contracted COVID-19.”

The findings also revealed a correlation between microstructural changes and symptom-specific brain networks associated with impaired cognition, sense of smell, and fatigue.

“Expression of post-COVID symptoms was associated with specific affected cerebral networks, suggesting a pathophysiological basis of this syndrome,” Dr. Rau said.

The researchers hope to reexamine the patients in the future, recording both clinical symptoms and changes to the brain’s microstructure.

Despite these brain imaging findings, it remains unclear why some people develop long COVID while others do not, although previous studies have identified risk factors including female sex, older age, higher body mass index, smoking, preexisting comorbidities, and previous hospitalization or intensive care unit admission.

Provided by Radiological Society of North America

Leave a Reply