By Paul McClure

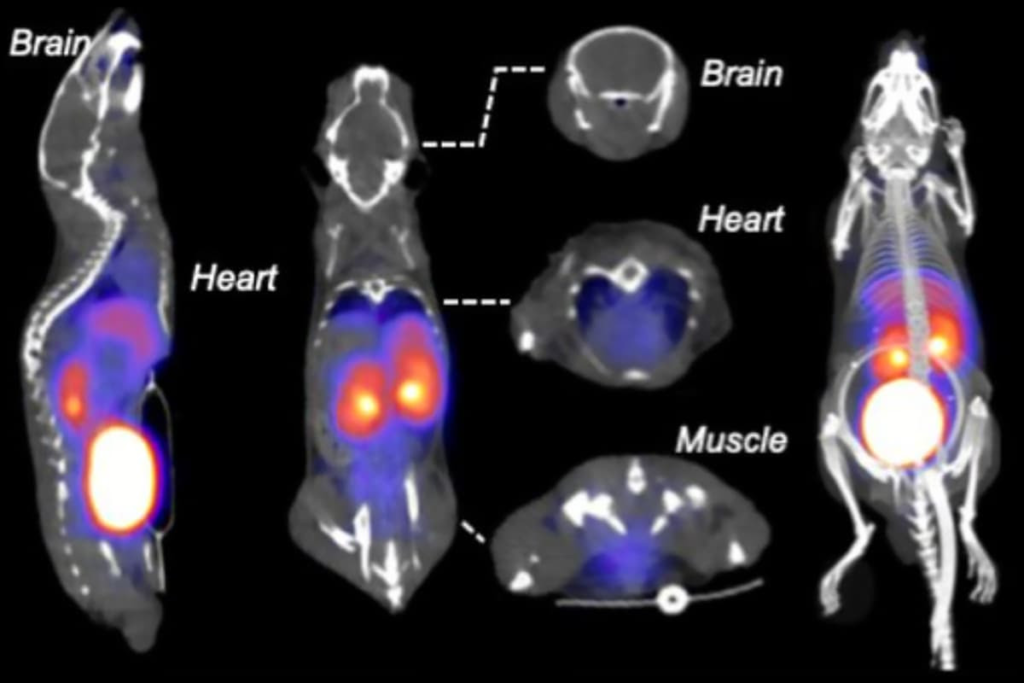

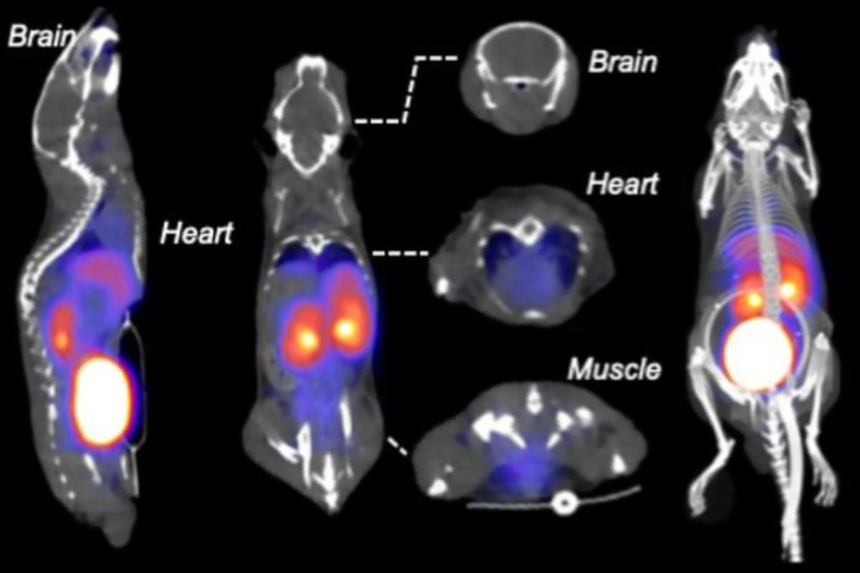

Radioactive fructose illuminated cancer cells and brain and heart inflammation on a PET scanKirby et al./Journal of Nuclear Medicine

A radioactive form of fructose, a natural sugar found in fruit, given to mice lit up areas of cancer and inflammation on a diagnostic medical scan. The researchers say the approach makes diseases easier to spot than current techniques and opens the door to new avenues of early detection.

A positron emission tomography or PET scan often relies on injecting a small amount of radioactive glucose, called a tracer, into the bloodstream. The scanner creates a picture based on where the glucose is used in the body. Since many cancers use glucose to fuel metabolism, it accumulates there, lighting the cancer up.

However, not all cancers use glucose for fuel, and healthy organs like the brain and heart can use it for energy, obscuring diseased areas on a PET scan. So, researchers from the University of Ottawa (uOttawa), Canada, developed a new radioactive tracer that instead maps how the cells use fructose, a type of sugar increasingly implicated in disease.

“For the first time, we can see where fructose, a common dietary sugar, is used in the body,” said Adam Shuhendler, corresponding author of the study. “Outside of the kidneys and the liver, fructose metabolism in any other organs may point to a sinister problem including cancer and inflammation.”

Like glucose, fructose is a simple sugar or monosaccharide. It’s found naturally in fruits (hence its alias, ‘fruit sugar’), fruit juices, some vegetables, and honey. And, like glucose, fructose is absorbed directly into the bloodstream from the small intestine. However, the liver needs to convert fructose to glucose before it can be used as energy.

Studies have found that when the heart tissue is starved of oxygen due to a heart attack, say, it switches to using fructose as an energy source. And evidence suggests that this switch may also be caused by inflammation and is a key driver of cancer growth. So, it makes sense to harness the diagnostic capabilities of fructose.

The researchers attached radioactive fluorine (18F), already widely used in PET scans, to a modified form of fructose to generate their novel tracer, [18F]4-FDF. When injected into a mouse model of human liver cancer, PET scans from 20 to 45 minutes after injection showed that the tracer accumulated in the tumor and less so in healthy tissues, the brain and the heart, suggesting that healthy organs have limited dependence on fructose as an energy source. In a mouse model of inflammation, scans showed a significant increase in heart and brain uptake of [18F]4-FDF, highlighting the tracer’s potential for sensitive inflammation mapping of these organs.

The discovery opens up new avenues for the earlier detection and treatment of cancers and inflammatory conditions affecting the heart and brain.

The study was published in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

Source: uOttawa

Leave a Reply