by Kerstin Wild, Leibniz Institute for Immunotherapy

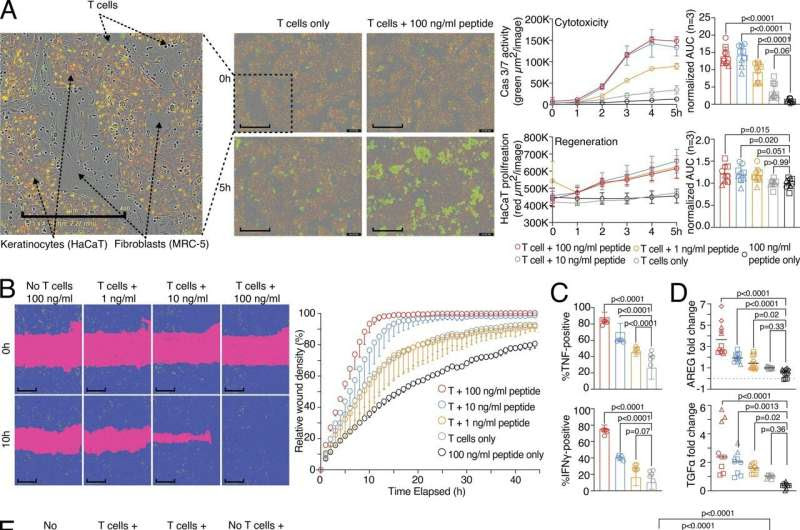

Wound healing and target killing are both effector mechanisms of CD8 T cells. (A) Combined proliferation and killing assay in the presence of influenza-specific CD8 T cells and varying amounts of pulsed peptides on MRC-5 and HaCaT cells seeded in a 30:70 ratio. Left, representative image with labels (0 versus 5 h; T cells only versus T cells + 100 ng/ml peptide). Right, representative quantification of Cas3/7 activity (green) and HaCaT proliferation (red) with titrated amounts of influenza peptide, with statistical verification across experiments using normalized area under the curve (AUC, n = 3, one-way ANOVA, symbols indicate individual experiments). Scale bars = 400 µm; enhanced for improved visibility. (B) SN from A tested in a wound healing assay with HaCaT cells; representative example with additional experiments in Fig. S1 (n = 3). Scale bars = 400 µm; enhanced for improved visibility. Reuse of the B panel in schematic of Fig. S1 A. (C) Measurement of intracellular TNF and IFN-γ in influenza-specific T cells used in the combined proliferation and killing assay, representative stainings (n = 12, one-way ANOVA), gating in Fig. S1. (D) Fold induction of AREG and TGFα in SNs from (A) (n = 3–4, one-way ANOVA, symbols indicate individual experiments) Individual experiments in Fig. S1. (E and F) Effect of using Cetuximab or anti-IFN-γ on wound healing capacity of SNs from (A) using background-corrected AUCs (n = 4, one-way ANOVA of AUC, symbols indicate individual experiments). Scale bars = 400 µm; enhanced for improved visibility. All data derived from three or more independent experiments. Credit: Journal of Experimental Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1084/jem.20230488

Researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Immunotherapy (LIT) have demonstrated that killer T cells of the immune system not only eliminate pathologically altered cells, but also promote the subsequent tissue wound healing process.

One of the main functions of the immune system is to defend the body against infections or cancer. This task is efficiently carried out by immune cells known as killer T cells. These cells possess the ability to destroy body cells that are, for example, infected by viruses or transformed into tumor cells. However, what happens after the destruction of infected body cells? How is tissue damage, resulting from the destruction of target cells, repaired, and organ function restored? These questions were examined in detail by the Immunology Division of the LIT.

The findings are published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“In wound healing experiments with human virus-specific killer T cells, we observed that after the destruction of infected cells, neighboring cells began to divide and fill the gap,” describes Michael Delacher, one of the authors of the study. In the experiments, a wound was created in a seeded cell layer. Culture supernatants from activated killer T cells caused this wound to close quickly.

“This indicates that soluble factors produced by killer T cells during the destruction of infected cells support the healing of the remaining tissue cells,” explains author Lisa Schmidleithner.

Which factors mediate this surprising healing property? The authors found that growth factors such as amphiregulin are involved in the wound healing effect. Human killer T cells can produce these growth factors and stimulate other cells in the tissue to produce them as well. In addition to these growth factors, “classic” immune messengers such as tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma can enhance the impact of amphiregulin and support the wound healing effect.

To better understand the impact of the regenerative effects of killer T cells, the researchers co-cultured human mini-organs, called organoids, with killer T cells.

“We observed that the number and size of these organoids significantly increased when activated killer T cells or their released growth factors were present,” reports author Philipp Stüve. This suggests that killer T cell-mediated wound healing processes can influence complex regeneration processes.

In addition to these positive effects on tissue regeneration and wound healing, the same killer T cell-derived growth factors could potentially promote diseases such as cancer. “Indeed, in further experiments, we observed that factors produced by activated killer T cells also enhanced the growth of tumor cells,” reports Malte Simon, who also authored the study.

What do these results mean for further research?

“Our data suggest that killer T cells not only destroy pathologically altered cells but also initiate the subsequent tissue regeneration,” explains Markus Feuerer, the lead author of the study. This mechanism could be useful in the context of viral infections to promote wound closure after the destruction of infected cells and thus restore functionality of the tissue. However, in the context of tumor diseases, this could promote the growth of undestroyed tumor cells.

Further research at the LIT must now clarify how to separate the destruction capacity from the wound-healing function of killer T cells. One possible approach is through so-called CAR T cell therapies, where killer T cells are genetically optimized to better destroy tumors. In the cell engineering process, it might be possible to delete the wound-healing capabilities of killer T cells.

More information: Michael Delacher et al, The effector program of human CD8 T cells supports tissue remodeling, Journal of Experimental Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1084/jem.20230488

Journal information: Journal of Experimental Medicine

Provided by Leibniz Institute for Immunotherapy

Leave a Reply