by Max Martin, University of Western Ontario

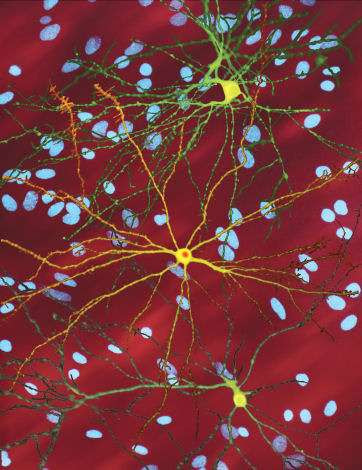

A montage of three images of single striatal neurons transfected with a disease-associated version of huntingtin, the protein that causes Huntington’s disease. Nuclei of untransfected neurons are seen in the background (blue). The neuron in the center (yellow) contains an abnormal intracellular accumulation of huntingtin called an inclusion body (orange). Credit: Wikipedia/ Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

A breakthrough genetic discovery from researchers at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at the University of Western Ontario is unlocking new clues about why some individuals experience early onset of neurodegenerative diseases.

A recent study led by the O’Donoghue Lab focused on mistakes that occur during the translation of gene products into proteins, allowing researchers to better understand genetic factors that affect disease.

Patrick O’Donoghue, Canada Research Chair in chemical biology, and his team examined mutations in transfer RNAs (tRNA), molecules essential for reading genetic blueprints that form the building blocks of key proteins in the body.

In a major leap forward for the field of research, the lab found in a previous study that the average human is born with 60-80 tRNA variants in their genetic makeup—previously, scientists around the world believed only one or two tRNA mutations existed in humans.

When mutations or variants are present in tRNAs, blueprints are misread, triggering errors in protein production in cells. Those errors, or mistranslations, show links to disease.

“If we can understand the molecular mechanisms behind a disease, we pave the way for finding treatments to mitigate damage or prevent debilitating diseases altogether,” explained Jeremy Lant, a Ph.D. candidate who was responsible for most of the project’s experimental work. “Our ultimate goal is to generate clinical impact for real people.”

Supporting bench-to-bedside translational research is a goal in the school’s new strategic plan.

The research now holds potential to shed light on the genetic causes of multiple neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and ALS, and to better determine factors that impact age of onset and severity of diseases like Huntington’s.

The findings could also provide insight into the causes of other life-threatening diseases like cancer.

“We are only just beginning to decipher how mistranslating tRNAs contribute to human diseases,” said Martin Duennwald, the project’s co-investigator and expert in Huntington’s disease models. “Moving forward, we need to develop new research tools to unravel the mechanics of tRNA mutants on protein aggregation in disease.”

To discover the dozens of previously unknown tRNA variants, the O’Donoghue Lab previously collaborated with other Western research groups to sequence the genes of all 610 tRNAs in the genomes of 80 individuals.

In the new study, the team honed in on particular tRNA mutations, examining how the variants could affect the progression of Huntington’s disease, a neurodegenerative condition characterized by the breakdown of nerve cells in the brain. It leads to difficulty in movement, speech impairment, and psychiatric disorders.

While Huntington’s disease has identifiable genetic causes, there are no known predictors for early onset or disease severity.

In a healthy body, cells maintain an efficient balance between creating proteins and then breaking them back down. But when cells affected by Huntington’s disease have the specific tRNA variant O’Donoghue’s team is studying, those cells become slower to clear away unneeded proteins.

That lag time results in the formation of large groups of disease-causing proteins that can’t be broken down.

For individuals who are genetically at-risk for Huntington’s disease, the tRNA variant may alter the age of onset or indicate more severe disease.

The specific variant is found in about two percent of the general population and could affect more than 100 million people worldwide.

The team also found cells with a certain tRNA variant were resistant to the integrated stress response inhibitor (ISRIB), a compound that may minimize the harmful effects of neurodegenerative diseases—a finding that holds implications for treatment protocols for patients.

The major discoveries made by the O’Donoghue Lab could be translated to countless other scientific and medical fields, with the potential to greatly impact patient care in the area of neurodegeneration.

“This knowledge will allow clinicians to pursue precise treatment options for patients with tRNA variants and neurodegenerative disease,” O’Donoghue said.

Leave a Reply