by Dartmouth College

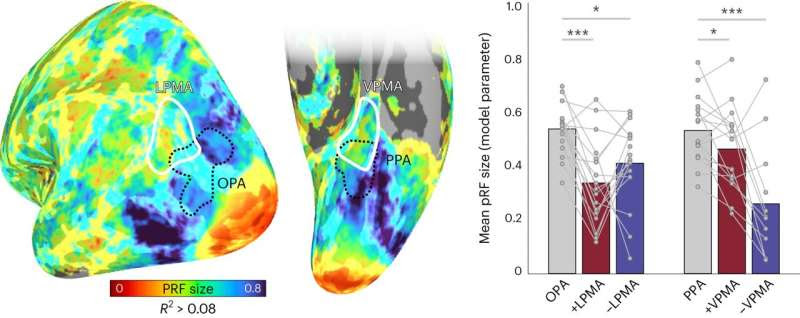

Memory areas contain smaller pRFs compared to their paired perceptual areas. Left, group average pRF size with memory areas and perception areas overlaid. Nodes are threshold at R2 > 0.08. Right, bars represent the mean pRF size for +pRFs in SPAs (OPA, PPA) and +/−pRFs in PMAs (LPMA, VPMA). Individual data points are shown for each participant. Across both surfaces, pRFs were significantly smaller on average in the PMAs than their perceptual counterparts. Credit: Nature Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-023-01512-3

Our memories are rich in detail: we can vividly recall the color of our home, the layout of our kitchen, or the front of our favorite café. How the brain encodes this information has long puzzled neuroscientists.

In a new Dartmouth-led study, researchers identified a neural coding mechanism that allows the transfer of information back and forth between perceptual regions to memory areas of the brain. The results are published in Nature Neuroscience.

Prior to this work, the classic understanding of brain organization was that perceptual regions of the brain represent the world “as it is,” with the brain’s visual cortex representing the external world based on how light falls on the retina, “retinotopically.” In contrast, it was thought that the brain’s memory areas represent information in an abstract format, stripped of details about its physical nature. However, according to the co-authors, this explanation fails to take into account that as information is encoded or recalled, these regions may in fact, share a common code in the brain.

“We found that memory-related brain areas encode the world like a ‘photographic negative’ in space,” says co-lead author Adam Steel, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences and fellow in the Neukom Institute for Computational Science at Dartmouth. “And that ‘negative’ is part of the mechanics that move information in and out of memory, and between perceptual and memory systems.”

In a series of experiments, participants were tested on perception and memory while their brain activity was recorded using a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. The team identified an opposing push-pull like coding mechanism, which governs the interaction between perceptual and memory areas in the brain.

The results showed that when light hits the retina, visual areas of the brain respond by increasing their activity to represent the pattern of light. Memory areas of the brain also respond to visual stimulation, but, unlike visual areas, their neural activity decreases when processing the same visual pattern.

The co-authors report that the study has three unusual findings. The first is their discovery that a visual coding principle is preserved in memory systems.

The second is that this visual code is upside-down in memory systems. “When you see something in your visual field, neurons in the visual cortex are driving while those in the memory system are quieted,” says senior author Caroline Robertson, an assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth.

Third, this relationship flips during memory recall. “If you close your eyes and remember that visual stimuli in the same space, you’ll flip the relationship: your memory system will be driving, suppressing the neurons in perceptual regions,” says Robertson.

“Our results provide a clear example of how shared visual information is used by memory systems to bring recalled memories in and out of focus,” says co-lead author Ed Silson, a lecturer of human cognitive neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh.

Moving forward, the team plans to explore how this push and pull dynamic between perception and memory may contribute to challenges in clinical conditions, including in Alzheimer’s.

More information: Adam Steel et al, A retinotopic code structures the interaction between perception and memory systems, Nature Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-023-01512-3

Journal information: Nature Neuroscience

Provided by Dartmouth College

Leave a Reply