Updated October 24, 2023

KEY POINTS

New research finds widely prescribed drugs are much less effective than their published record suggests.

One study saw financial conflicts of interest driving whether unfavorable results were reported and where.

A new study of FDA data finds the recorded efficacy of alprazolam XR inflated by more than 40 percent.

Source: Iren Moroz / ShutterstockSource: Iren Moroz / Shutterstock

Earlier this summer, three distinguished researchers set out to determine if publication bias over the handling of unfavorable results could be quantified precisely.

When uncounted negative data are reintroduced into datasets and swollen effect sizes, however, flags appear over the published record on which researchers, practitioners, and patients all rely heavily.

Unfavorable Results

In the August issue of the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, Martin Plöderl of Salzburg’s Paracelsus Medical University and Simone Amendola and Michael P. Hengartner at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences re-examined 27 observational studies that had previously assessed associations between antidepressant use and increases in suicidal behavior.

In “Observational studies of antidepressant use and suicide risk are selectively published in psychiatric journals,” their open-access article, re-examination of the original data shows that “studies published in nonpsychiatric journals indicate that antidepressant-use is associated with significantly increased suicide risk.” By contrast, “studies published in psychiatric journals report inconclusive results close to the null effect.”

Plöderl, Amendola, and Hengartner found similarly strong evidence that:

lead authors with financial conflicts of interest (fCOI) published more favorable results than lead authors without ties to the pharmaceutical industry;

lead-authors with fCOI published their studies in psychiatric journals with higher impact factor (IF) and rank than did lead authors without ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

As one of several hypotheses for the measurable bias, Plöderl, Amendola, and Hengartner point to “the firm belief that [with antidepressants] benefits outweigh harms may lead to selective publication of favorable results, especially by authors with financial conflicts of interest (fCOI).”

Former University of Copenhagen professor Peter C. Gøtzsche extrapolated the resulting P-value for Med Twitter: “Psychiatrists who take money from drug companies publish studies in psychiatric journals that do not show an increased risk of suicide with depression drugs, in contrast to other researchers (P < 0.01 for the difference).Undetected and Underreported Harms.

Nine of the 27 studies (33 percent) re-examined involved lead authors with financial conflicts of interest. On statistical significance alone, however, none of the 27 (0 percent) produced favorable results—that is, evidence of reduced suicide risk from antidepressants. Ten of the studies (37 percent) were classified as unclear (inconclusive), while 17 (63 percent) led to unfavorable results (that is, showed increased suicide risk with antidepressants).

“We further found evidence of selective publication,” Plöderl, Amendola, and Hengartner continue; “the association between antidepressant use and increased suicide risk became substantially stronger after imputing missing studies with trim-and-fill procedure.”

In ways that skew the record and evidence base, “potential harms may still go undetected because, in publications of RCTs [randomized controlled trials], the analysis of safety data is largely inadequate and harms are often underreported.”

Extrapolating from the data while correcting for its bias, the researchers conclude: “The best evidence from meta-analyses of RCTs and observational studies indicates that antidepressant use has no clear effect on suicidal behavior or that it may even increase the suicide risk.”

“Our study has some limitations,” they note. “Foremost, the study samples were too small for some subgroup analyses, thus inflating the risk of both type I and type II errors. [And] for about one-third of the studies, we did not receive feedback from the authors, thus the findings about publication history and difficulty of publishing must be interpreted with caution.”

“I would not be surprised about similar biases in other medical fields and also in psychotherapy or clinical psychology,” Plöderl tells me over email when invited to comment on his study’s broader implications. “It seems that self-correction, such as publishing inconvenient findings, is not adequately done. Independent research and pre-registered studies may improve the situation. Further, conflicts of interest with the industry should be taken more seriously. That antidepressant use may increase suicide risk can pose a serious public health issue, given the widespread prescription of these drugs and unsubstantiated claims to the contrary within academic psychiatry.”

As Effective as We Thought?

Study authors who stonewall investigation into the reliability of their data remain a concern in a strikingly similar study on publication bias, released last week in Psychological Medicine.In “Unpublished trials of alprazolam XR and their influence on its apparent efficacy for panic disorder,” Erick Turner, M.D., professor of psychiatry at the Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine and a former US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviewer, and co-author Rosa Ahn-Horst, M.D., M.P.H., a resident in psychiatry at Harvard University, reviewed “publicly available FDA data from phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials conducted for extended-release alprazolam for the treatment of panic disorder to determine how much publication bias inflated the drug’s apparent efficacy.”

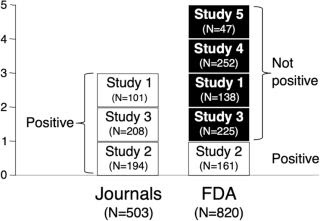

Ahn-Horst and Turner (2023), fig. 1, with full permission.

Alprazolam XR trial outcomes as presented by journal articles v. FDA.Source: Ahn-Horst and Turner (2023), fig. 1, with full permission.

Of the five trials conducted, only three had been published in medical journals and only one of them (20 percent) produced positive results. “Of the four not-positive trials, two had been published incorrectly as conveying positive outcomes, and the other two were not published. Thus, according to the published literature, three trials were conducted and all (100%) were positive.”

Just as notable, the one study (#2) that the FDA “deemed clearly positive” involved an “irregularity at one of [its] study sites.” Inspection for an FDA review flagged that “28 of 37 subject records were not available for review,” because the lead researcher “had destroyed these records in March 1999.” As such, “validity of the data reported could not be verified.”

Even so, the FDA’s review division concluded in 2003, when approving alprazolam’s extended-release formulation for panic disorder, “These results do not change the conclusion.” Not even after the “above-mentioned investigator was included as a co-author, as were the data from his site.”

In a theme that echoes Plöderl, Amendola, and Hengartner’s study on inflated efficacy and minimized harms in antidepressants, Ahn-Horst and Turner write that “according to the published literature, every trial of alprazolam XR found it to be effective. By contrast, according to the FDA, only one of five trials was positive. Consequently, the effect size derived from the FDA data was substantially lower than the effect size from the published literature.”

They determined that publication bias “inflated the efficacy of the commonly prescribed benzodiazepine by 42 percent.”

A Widely-Prescribed Sedative

Alprazolam (Xanax) XR is now “prescribed to more than 5 percent of U.S. adults and involved in nearly 14 percent of fatal opioid overdoses, potentiating their lethality.”

“Clinicians are well aware of the safety issues,” Turner explains in follow-up comments on the study, “but there’s been essentially no questioning of their effectiveness… Our study throws some cold water on the efficacy of this drug. It shows it may be less effective than people have assumed.”

Indeed, as he and Ahn-Horst quantify, these latest findings “alter the risk-benefit ratio for the prescribing of this benzodiazepine, especially in the light of recent attention to their contribution to the opioid crisis and the availability of safer alternatives.”

“This study will reinforce being cautious about starting a prescription,” Turner advises over email. “The conventional wisdom is that benzodiazepines are very effective, a belief facilitated by publication bias. In the articles published for the benefit of doctors and researchers, it appeared that the drug was effective in every trial. However, our examination of FDA data revealed that, as we’ve seen with other drugs, unflattering clinical trial results were either spun into something positive or simply not published. Of five trials, only one was deemed clearly positive by the FDA.”

“This raises the question, Is Xanax XR as effective as we have thought it to be? And that, in turn, raises the question, When the patient considers requesting—or the doctor contemplates prescribing—Xanax for panic disorder, how confident should they be that it will meaningfully reduce the symptoms?”

Conclusions

Anomalies such as these have been well-documented for years (Hengartner; Ioannidis; Isacsson and Rich; Jureidini and McHenry; and Smith). Yet, even in that context, the information from these latest studies—of significant publication bias over antidepressant use and suicide risk, and of highly inflated efficacy for a widely prescribed benzodiazepine—is controversial and needs further investigation.

Considering Turner’s experience as an FDA reviewer, including that he tells me the agency “does not base its decisions as to sufficient efficacy on meta-analysis or effect size, but rather on the statistically primitive method of counting the number of positive studies (and number of negative studies),” the kind of investigation that could lead to a complete recall of alprazolam XR seems unlikely.

Nevertheless, historically, the agency has “needed two positive short-term studies for them to call it “substantial evidence of effectiveness”—a phrase used in the Code of Federal Regulations. And in the case of alprazolam XR, Turner underscores, “what was unusual was for a single positive study to suffice for approval.”

He believes, based on wording in the FDA statistical review, that “the FDA moved the goalposts—to the sponsor’s benefit—sometime during the time this new drug application was under review.”

When the sponsor in question—Upjohn Pharmaceuticals—is also known to have paid for the original studies and the DSM-III meeting in Boston at which panic disorder was approved as a stand-alone disorder, based on criteria shared with the drug-maker, over strong objections to the reliability of its data, we can detect a chain of decisions that, based on evidence alone, almost certainly should have gone the other way.

References

Ahn-Horst R, and Turner E. (Oct. 2023). Unpublished trials of alprazolam XR and their influence on its apparent efficacy for panic disorder. Psychological Medicine, 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0033291723002830

Hengartner MP. (2021). Evidence-Based Antidepressant Prescription: Overmedicalisation, Flawed Research, and Conflicts of Interest. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Ioannidis JP (2016). Evidence-based medicine has been hijacked: a report to David Sackett. J Clin Epidemiol 73. 82–86. doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.02.012

Leave a Reply