September 18, 2024

by McGill University

Credit: Jonathan Gallego Rudolf

Amyloid-beta and tau proteins have long been associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The pathological buildup of these proteins leads to cognitive decline in people with the disease. How it does that, though, remains poorly understood.

A new study from the labs of Sylvain Baillet at The Neuro and Sylvia Villeneuve at the Douglas Research Centre provides important insight into how these proteins impact brain activity and possibly contribute to cognitive decline. Their findings were published in a paper titled “Synergistic association of Aβ and tau pathology with cortical neurophysiology and cognitive decline in asymptomatic older adults” in the journal Nature Neuroscience on Sept. 18, 2024.

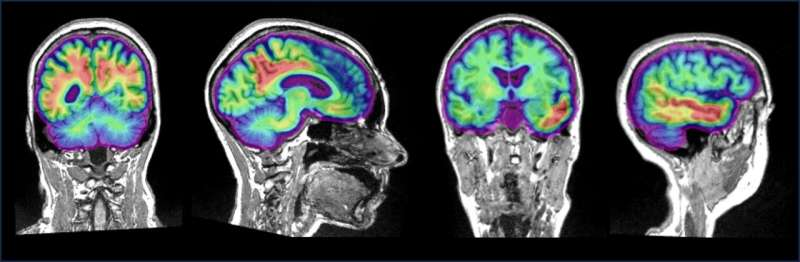

The team led by Jonathan Gallego Rudolf, a Ph.D. candidate in Baillet and Villeneuve’s labs, recruited 104 people with a family history of Alzheimer’s. They scanned the participants’ brains using a combination of positron emission tomography (PET) to detect the presence and location of the proteins and magnetoencephalography (MEG) to record brain activity in these regions.

The scientists compared the results of the two scans and found that brain areas with increased levels of amyloid-beta showed macroscopic expressions of brain hyperactivity, reflected by increased fast- and decreased slow-frequency brain activity. For people with both amyloid-beta and tau in their brain, the pattern shifted towards hypoactivity, with higher levels of pathology leading to brain activity slowing.

Understanding changes in pre-clinical Alzheimer’s diseaseMagnetoencephalography records magnetic fields produced by electrical currents occurring naturally in the brain. Credit: Jonathan Gallego Rudolf

Using cognitive tests, the team discovered that participants with higher rates of this amyloid-tau related brain slowing showed higher levels of decline in attention and memory.

The findings suggest that the interplay between amyloid-beta and tau lead to altered brain activity before noticeable cognitive symptoms appear. In a follow-up study, Rudolf plans to rescan the same participants over time to prove whether the accumulation of the two proteins promotes further slowing of brain activity, and whether this accurately predicts the cognitive evolution of the participants.

“Our study provides direct evidence in humans for the hypothesized shift in neurophysiological activity, from neural hyper- to hypo-activity, and its association with longitudinal cognitive decline. These results parallel findings from animal and computational models and contribute to the advancement of our understanding of the pathological mechanisms underlying the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Rudolf.

More information: Synergistic association of Aβ and tau pathology with cortical neurophysiology and cognitive decline in asymptomatic older adults, Nature Neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-024-01763-8

Journal information: Nature Neuroscience

Provided by McGill University

Leave a Reply