by Stanford University Medical Center

Credit: Journal of Psychiatric Research (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.08.002

Many people who dream of an organized, uncluttered home à la Marie Kondo find it hard to decide what to keep and what to let go. But for those with hoarding disorder—a mental condition estimated to affect 2.5% of the U.S. population—the reluctance to let go can reach dangerous and debilitating levels.

Now, a pilot study by Stanford Medicine researchers suggests that a virtual reality therapy that allows those with hoarding disorder to rehearse relinquishing possessions in a simulation of their own home could help them declutter in real life. The simulations can help patients practice organizational and decision-making skills learned in cognitive behavioral therapy—currently the standard treatment—and desensitize them to the distress they feel when discarding.

The study was published in the October issue of the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

A hidden problem

Hoarding disorder is an under-recognized and under-treated condition that has been included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—referred to as the DSM-5—as a formal diagnosis only since 2013. People with the disorder, who tend to be older, have persistent difficulty parting with possessions, resulting in an accumulation of clutter that impairs their relationships, their work and even their safety.

“Unfortunately, stigma and shame prevent people from seeking help for hoarding disorder,” said Carolyn Rodriguez, MD, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and senior author of the study. “They may also be unwilling to have anyone else enter the home to help.”

Sometimes the condition is discovered through cluttered backgrounds on Zoom calls or, tragically, when firefighters respond to a fire, Rodriguez said. Precarious piles of stuff not only prevent people from sleeping in their beds and cooking in their kitchens, but they can also attract pests; block fire exits; and collapse on occupants, first responders and clinicians offering treatment.

Clinicians like Rodriguez occasionally make home visits to help patients practice parting with possessions, but some homes are off limits.

“Some people are in such dire need, but we can’t go into their homes. The clutter is stacked so high that it’s dangerous for our team to go inside,” Rodriguez said. “Yet, practicing letting go of items is such a useful skill that we wanted to create a virtual and safe environment.”

Virtual stepping stone

In the study, Rodriguez’s team asked nine participants, over the age of 55 and with diagnosed hoarding disorder, to take photos and videos of the most cluttered room in their home along with 30 possessions. With the help of a VR company and Stanford University engineering students, the photos and videos were transformed into custom 3D virtual environments. The participants navigated around their rooms and manipulated their possessions using VR headsets and handheld controllers.

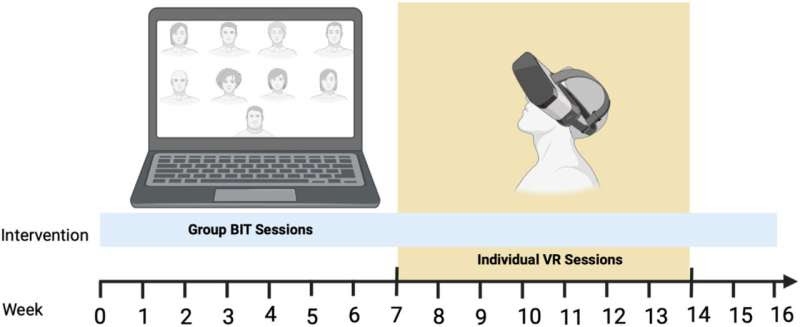

All participants attended 16 weeks of online facilitated group therapy that provided peer support and cognitive behavioral skills related to hoarding. In weeks seven to 14, they also received individual VR sessions guided by a clinician. In these one-hour sessions, they learned to better understand their attachment to the objects and practiced placing them in recycling, donation or trash bins—the latter of which was taken away by a virtual garbage truck. They were then assigned the task of discarding the actual item at home.

As with many mental health disorders, the causes of hoarding disorder are not well understood, Rodriguez said, but could involve difficulty processing information, making decisions, sustaining attention or regulating emotions. People with the disorder may fear a loss of security or identity giving up their treasured possessions.

The virtual experience can serve as “a kind of stepping stone,” a less intense version of real-life discarding, Rodriguez said. “It’s nice to be able to titrate in a virtual space for people who experience considerable distress even attempting to part with possessions.”

Seven of the nine participants improved in self-reported hoarding symptoms, with an average decrease of 25%. Eight of nine participants also had less clutter in their homes based on visual assessment by clinicians, with an average decrease of 15%. These improvements are comparable to those from group therapy alone, so it’s still unclear whether VR therapy can add value, Rodriguez said. But importantly, this small initial trial demonstrated that VR therapy for hoarding disorder is feasible and well-tolerated, even in older patients.

“I actually thought it might not work because these were older patients and maybe they would not like the technology or they would be dizzy—but they thought it was fun,” she said.

Most participants said VR decluttering helped them part with possessions in real life, though some found the VR experience unrealistic. The researchers hope that newer technology will improve the VR experience and perhaps allow augmented reality, in which virtual objects are overlaid in the patient’s real home.

“People tend to have a lot of biases against hoarding disorder and see it as a personal limitation instead of a neurobiological entity,” Rodriguez said. “We just really want to get the word out that there’s hope and treatment for people who suffer from this. They don’t have to go it alone.”

More information: Hannah Raila et al, Augmenting group hoarding disorder treatment with virtual reality discarding: A pilot study in older adults, Journal of Psychiatric Research (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.08.002

Journal information: Journal of Psychiatric Research

Provided by Stanford University Medical Center

Explore further

New guidance to help diagnose hoarding disorder

Leave a Reply