by Christoph Elhardt, ETH Zurich

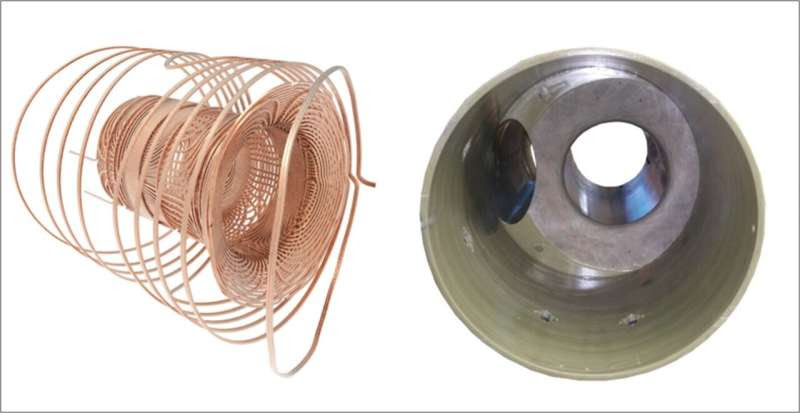

The coils that generate the magnetic field (left) and a visualization of the entire scanner (right). Credit: ETH Zurich

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurological disease that usually leads to permanent disabilities. It affects about 2.9 million people worldwide, and about 15,000 in Switzerland alone. One key feature of the disease is that it causes the patient’s own immune system to attack and destroy the myelin sheaths in the central nervous system.

These protective sheaths insulate the nerve fibers, much like the plastic coating around a copper wire. Myelin sheaths ensure that electrical impulses travel quickly and efficiently from nerve cell to nerve cell. If they are damaged or become thinner, this can lead to irreversible visual, speech and coordination disorders.

So far, however, it hasn’t been possible to visualize the myelin sheaths well enough to reliably diagnose and treat MS. Now researchers at ETH Zurich, led by Markus Weiger and Emily Baadsvik from the Institute for Biomedical Engineering, have developed a new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedure that maps the condition of the myelin sheaths more accurately than was previously possible. The researchers successfully tested the procedure on healthy people for the first time.

Their research has resulted in two articles, one published in Science Advances and one published in Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

In the future, the MRI system with its special head scanner could help doctors to recognize MS at an early stage and better monitor the progression of the disease. The technology could also facilitate the development of new drugs for MS. But it doesn’t end there: the new MRI method could also be used by researchers to better visualize other solid tissue types such as connective tissue, tendons and ligaments.

Quantitative myelin maps

Conventional MRI devices capture only inaccurate, indirect images of the myelin sheaths. That’s because most of these devices work by reacting to water molecules in the body that have been stimulated by radio waves in a strong magnetic field. But the myelin sheaths, which wrap around the nerve fibers in several layers, consist mainly of fatty tissue and proteins.

That said, there is some water—known as myelin water—trapped between these layers. Standard MRIs build their images primarily using the signals of the hydrogen atoms in this myelin water, rather than imaging the myelin sheaths directly.

The ETH researchers’ new MRI method solves this problem and measures the myelin content directly. It puts numerical values on MRI images of the brain to show how much myelin is present in a particular area compared to other areas of the image. A number 8, for instance, means that the myelin content at this point is only 8% of a maximum value of 100, which indicates a significant thinning of the myelin sheaths.

Essentially, the darker the area and the smaller the number in the image, the more the myelin sheaths have been reduced. This information ought to enable doctors to better assess the severity and progression of MS.

Measuring signals within millionths of a second

However, it is difficult to image the myelin sheaths directly. That’s because the signals that the MRI triggers in the tissue are very short-lived; the signals that emanate from the myelin water last much longer.

More information: Emily Louise Baadsvik et al, Quantitative magnetic resonance mapping of the myelin bilayer reflects pathology in multiple sclerosis brain tissue, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi0611

Emily Louise Baadsvik et al, Myelin bilayer mapping in the human brain in vivo, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2024). DOI: 10.1002/mrm.29998

Provided by ETH Zurich

Leave a Reply