September 17, 2024

by Nottingham Trent University

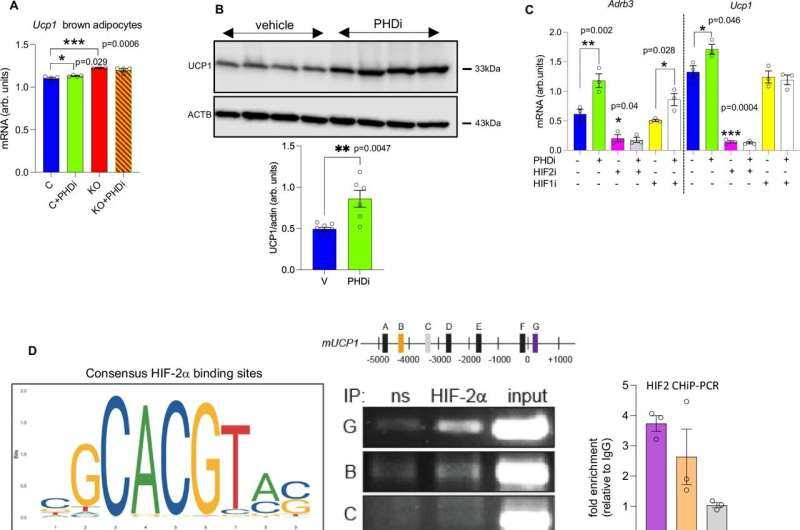

Pharmacological pan-PHD inhibition induces Ucp1 expression in mouse and human adipocytes in vitro. Credit: Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51718-7

Removing a specific gene from fat tissue could fool the body into speeding up metabolism and burning more calories, a new study has found.

It is hoped that the research, led by scientists at Nottingham Trent University and the University of Edinburgh, could help pave the way for protecting against the metabolic diseases that often come with obesity, such as type 2 diabetes. The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

The study focused on the gene “PHD2” which is found at high levels in brown adipose tissue, a type of body fat that is activated in cold temperatures to help keep us warm.

Brown fat helps the body to burn calories, breaking down blood sugar and fat molecules to create heat and maintain body temperature.

The research was prompted by the idea that people often lose weight and have a faster metabolic rate in higher altitudes, where it is cooler and there is low oxygen.

As such, the team focused their work on PHD2, which works as an oxygen sensor for the body and plays an important role in the regulation of brown fat.

By removing the gene in the brown fat of mice, the researchers discovered that they were able to mimic the high altitude effect on fat and make the tissue believe it was hypoxic—when lower levels of oxygen reach the tissue.

Importantly, the researchers were able to achieve this effect in a warm environment under conditions where brown fat is normally suppressed.

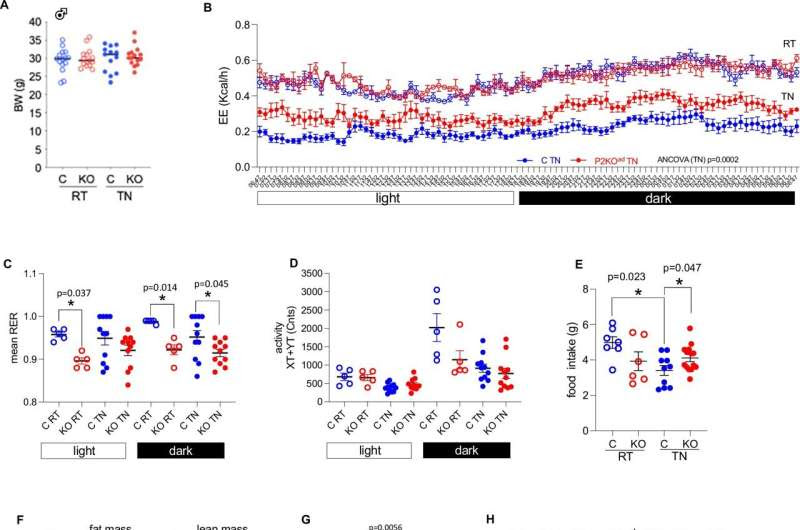

Adipose-Phd2 deletion in male mice sustains higher energy expenditure at thermoneutrality. Credit: Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51718-7

The study showed that, despite eating significantly more, the mice without the gene burned predominantly more fat and 60% more calories than mice with the gene.

The researchers also observed that signs of poor metabolic health typically associated with excess weight were not found in mice without the gene.

As part of the study, the team also analyzed blood from more than 5,000 participants, revealing that levels of the PHD2 protein were higher in those who carried more fat around their stomach and that the gene was associated with an increased risk of metabolic disease.

The team argues that inhibiting the oxygen sensing gene could help protect the body from type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

“Brown fat is a special kind of calorie burning tissue more active in humans when they are exposed to cold temperatures,” said senior author Dr. Zoi Michailidou, a researcher in Nottingham Trent University’s School of Science and Technology.

She said, “By removing a protein that lets fat cells sense oxygen, we have been able to show that calorie burning could happen in mice and human cells even when they are not exposed to cold temperatures.

“Reducing this protein’s effect may break the link between being overweight and type 2 diabetes, meaning our findings could be important for people with an increased risk of this disease.

“Although it is early days and more research is required in people, targeting this key protein could open up new strategies to sustain weight loss by increasing metabolism and without the need for continuous dieting.”

More information: Rongling Wang et al, Adipocyte deletion of the oxygen-sensor PHD2 sustains elevated energy expenditure at thermoneutrality, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51718-7

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Nottingham Trent University

Leave a Reply