Perspective > Medscape > Impact Factor with F. Perry Wilson

COMMENTARY

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Disclosures November 20, 2023

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Robert Louis Stevenson famously said, “Wine is bottled poetry.” And I think it works quite well. I’ve had wines that are simple, elegant, and unpretentious like Emily Dickinson, and passionate and mysterious like Pablo Neruda. And I’ve had wines that are more analogous to the limerick you might read scrawled on a rest-stop bathroom wall. Those ones give me headaches.

Wine headaches are on my mind this week, not only because of the incoming tide of Beaujolais nouveau, but because of a new study which claims to have finally explained the link between wine consumption and headaches — and apparently it’s not just the alcohol.

Headaches are common, and headaches after drinking alcohol are particularly common. An interesting epidemiologic phenomenon, not yet adequately explained, is why red wine is associated with more headache than other forms of alcohol. There have been many studies fingering many suspects, from sulfites to tannins to various phenolic compounds, but none have really provided a concrete explanation for what might be going on.

A new hypothesis came to the fore this week in the journal Scientific Reports:

To understand the idea, first a reminder of what happens when you drink alcohol, physiologically.

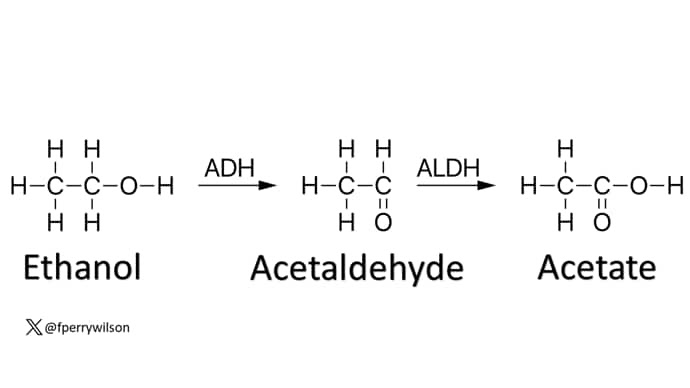

Alcohol is metabolized by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the gut and then in the liver. That turns it into acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite. In most of us, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) quickly metabolizes acetaldehyde to the inert acetate, which can be safely excreted.

I say “most of us” because some populations, particularly those with East Asian ancestry, have a mutation in the ALDH gene which can lead to accumulation of toxic acetaldehyde with alcohol consumption — leading to facial flushing, nausea, and headache.

We can also inhibit the enzyme medically. That’s what the drug disulfiram, also known as Antabuse, does. It doesn’t prevent you from wanting to drink; it makes the consequences of drinking incredibly aversive.

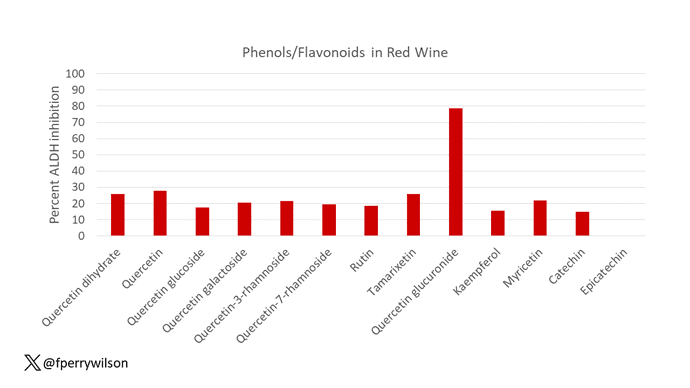

The researchers focused in on the aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme and conducted a screening study. Are there any compounds in red wine that naturally inhibit ALDH?

The results pointed squarely at quercetin, and particularly its metabolite quercetin glucuronide, which, at 20 micromolar concentrations, inhibited about 80% of ALDH activity.

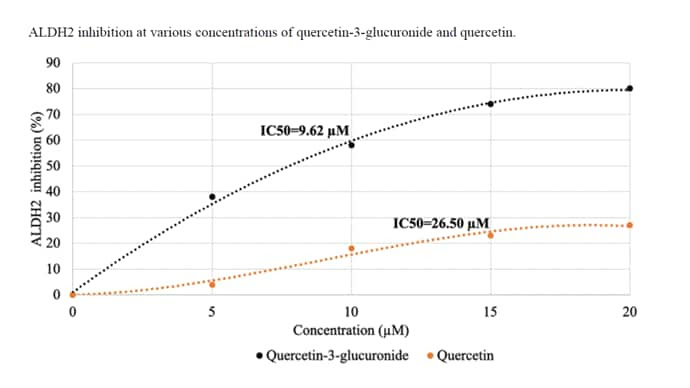

Quercetin is a flavonoid — a compound that gives color to a variety of vegetables and fruits, including grapes. In a test tube, it is an antioxidant, which is enough evidence to spawn a small quercetin-as-supplement industry, but there is no convincing evidence that it is medically useful. The authors then examined the concentration of quercetin glucuronide to achieve various inhibitions of ALDH, as you can see in this graph here.

By about 10 micromolar, we see a decent amount of inhibition. Disulfiram is about 10 times more potent than that, but then again, you don’t drink three glasses of disulfiram with Thanksgiving dinner.

This is where this study stops. But it obviously tells us very little about what might be happening in the human body. For that, we need to ask the question: Can we get our quercetin levels to 10 micromolar? Is that remotely achievable?

Let’s start with how much quercetin there is in red wine. Like all things wine, it varies, but this study examining Australian wines found mean concentrations of 11 mg/L. The highest value I saw was close to 50 mg/L.

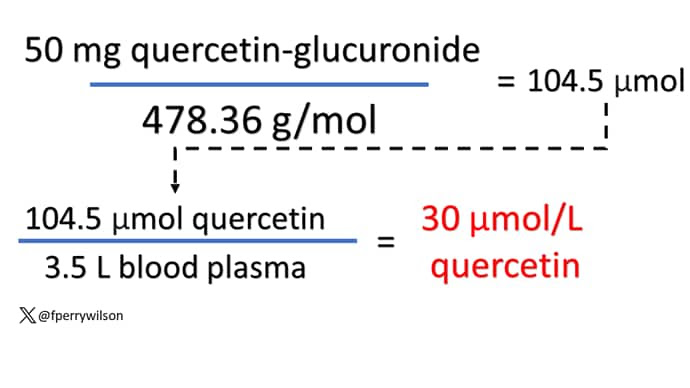

So let’s do some math. To make the numbers easy, let’s say you drank a liter of Australian wine, taking in 50 mg of quercetin glucuronide.

How much of that gets into your bloodstream? Some studies suggest a bioavailability of less than 1%, which basically means none and should probably put the quercetin hypothesis to bed. But there is some variation here too; it seems to depend on the form of quercetin you ingest.

Let’s say all 50 mg gets into your bloodstream. What blood concentration would that lead to? Well, I’ll keep the stoichiometry in the graphics and just say that if we assume that the volume of distribution of the compound is restricted to plasma alone, then you could achieve similar concentrations to what was done in petri dishes during this study.

Of course, if quercetin is really the culprit behind red wine headache, I have some questions: Why aren’t the Amazon reviews of quercetin supplements chock full of warnings not to take them with alcohol? And other foods have way higher quercetin concentration than wine, but you don’t hear people warning not to take your red onions with alcohol, or your capers, or lingonberries.

There’s some more work to be done here — most importantly, some human studies. Let’s give people wine with different amounts of quercetin and see what happens. Sign me up. Seriously.

As for Thanksgiving, it’s worth noting that cranberries have a lot of quercetin in them. So between the cranberry sauce, the Beaujolais, and your uncle ranting about the contrails again, the probability of headache is pretty darn high. Stay safe out there, and Happy Thanksgiving.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and YouTube

Leave a Reply